TALLY ENTRIES 711-720

I commented in an earlier entry that, as I wind down my visual comet observing efforts towards what will likely be a full "retirement" within the not-too-distant future, several of my "old friend" periodic comets are stopping by for one last visit. Such is certainly the case with this comet, which I saw for the first time over four decades ago. I discuss its overall history, as well as my own personal history with it, in its "Countdown" entry for its 2008 return (no. 436); since that time, I also managed to observe it on two occasions durings its very unfavorable return in 2015 (no. 585), these taking place over four months past perihelion by which time it had become a very faint and diffuse object near 13th magnitude. With this current return Comet Borrelly becomes only the third periodic comet (after 2P/Encke and 81P/Wild 2) that I have seen on seven different returns, and it is also one of only seven comets that have been visited by spacecraft, this having been accomplished by NASA's Deep Space 1 mission during the comet's return in 2001 (no. 292).

Following its 2015 return Comet Borrelly passed 0.44 AU from Jupiter in May 2019, which decreased its perihelion distance from 1.35 AU to its present 1.31 AU but left most of the other orbital parameters basically unchanged. Since it was observed when near aphelion prior to its 2001 return it can be considered an "annual" comet and thus is not "recovered" in the traditional sense of that term; the earliest observations during the present return were obtained by the ATLAS program in Hawaii on June 20, 2001, and by several other entities over the next few nights. The comet has remained fairly deep in southern skies ever since that time, reaching a peak southerly declination near -59 degrees during late September; around that time the first visual observations, near 14th magnitude, began to be reported by observers in the southern hemisphere. For the past few weeks it has been traveling northward and brightening, and meanwhile various CCD images I have seen -- including a recent set I obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network -- have been showing a distinct "anti-tail" feature. I made my first visual attempt on the evening of November 28 -- at which time its declination was -39 degrees -- and saw it rather easily as a moderately condensed object just fainter than magnitude 11 1/2. I didn't detect this "anti-tail," although since it is rather faint I didn't expect to.

LEFT: The nucleus of Comet 19P/Borrelly (a bowling-pin shaped object roughly 8 km by 4 km across), as imaged by NASA's Deep Space 1 spacecraft on September 22, 2001. Courtesy NASA. RIGHT: An image of Comet Borrelly I obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile on November 24, 2021. The "anti-tail" can faintly be seen extending towards the upper left.

LEFT: The nucleus of Comet 19P/Borrelly (a bowling-pin shaped object roughly 8 km by 4 km across), as imaged by NASA's Deep Space 1 spacecraft on September 22, 2001. Courtesy NASA. RIGHT: An image of Comet Borrelly I obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile on November 24, 2021. The "anti-tail" can faintly be seen extending towards the upper left.

The current return of Comet Borrelly is a moderately favorable one -- indeed, it is the best one thus far of the 21st Century -- and although it is presently located deep in my southern sky the viewing circumstances (for the northern hemisphere, anyway) will become much better over the coming weeks. At this time it is in southwestern Sculptor about a degree west of the star Beta Sculptoris and is traveling towards the north-northeast at approximately 40 arcminutes per day; it is nearest Earth (1.17 AU) shortly before mid-December. It crosses into Cetus late that month, into eastern Pisces at the end of January 2022, into Aries during the second week of February, and -- curving more directly eastward -- into Perseus shortly after mid-March then into Auriga in early April. The comet crosses north of declination +40 degrees just before the middle of that month and reaches a peak northerly declination of +43 degrees a month later, thereafter curving gradually towards the east-southeast as it crosses into Lynx during the latter part of May and into Leo Minor shortly before the end of June, by which time it will be starting to get low in the northwestern sky after dusk. Based upon its behavior during previous returns, I expect a peak brightness between 9th and 10th magnitude during January and February, and I should be able to follow it visually until sometime in April or May.

I commented in Comet Borrelly's "Countdown" entry that this current return is relatively similar to the return in 1981 (no. 43), the first return during which I observed it. I also mentioned that that return came during one of the darkest times of my life, and expressed the hope that that wouldn't be the case this time around. For the most part, I would say that that is true; while I continue to be plagued by the health issues that have played a non-trivial role in my recent decision to "semi-retire," and eventually to fully "retire," from visual comet observing, overall I am relatively content with where my life is right now. My life with Vickie is quite pleasant, and among other things I was able to spend quality time with both of my sons and my new grandson when they all visited during this past holiday weekend. I have recently become involved with an educational effort that offers the potential for good opportunities for both me personally and for Earthrise; at this time, however, this is not much more than a possibility, and I will have to wait and see whether or not it comes to fruition. I will have more to say about that effort if and when it becomes a reality.

It so happens that Comet Borrelly's next return, in 2028 (perihelion early December), is very favorable: the comet passes just 0.41 AU from Earth -- the closest approach it will have made to our planet since its discovery in 1904 -- and it should reach at least 7th magnitude. While this is well after the "retirement" timeframe that I have discussed in various previous entries, I plan to always reserve to myself the right to "come out of retirement" on brief occasions for bright or otherwise interesting comets, so -- depending upon my health and other life circumstances at that time -- it is conceivable that I might observe Comet Borrelly then. The return after that, in 2035 (perihelion late October, with a minimum distance from Earth of 0.62 AU), is also quite favorable, and the comet should reach about 8th magnitude. That is too far into the future for me to give any thought to at this time, but if I'm still alive then and still actively involved in astronomy in any way, we'll see what happens . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 November 29.10 UT, m1 = 11.7, 1.6' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

712. COMET 104P/KOWAL 2 Perihelion: 2022 January 11.62, q = 1.073 AU

As 2021 approaches its conclusion I was able to squeeze one more comet into my tally before year's end. The comet in question is a short-period object that I have seen on two previous returns, and was originally discovered in January 1979 by American astronomer Charles Kowal, who from the early 1970s through the mid-1980s conducted a regular survey program with the 1.2-meter (48-inch) Schmidt telescope at Palomar Observatory in California. During the course of this program Kowal discovered five comets (all of short-period, some of which were independently found by other discoverers, and all of which have since been recovered and numbered), two "X/" comets, i.e., comets which were too poorly observed to have valid orbital calculations performed, and, in 1977, the first-recognized Centaur, (2060) Chiron, which exhibited cometary activity as it approached perihelion in 1996 and was accordingly dual-designated as Comet 95P, and which I followed for three years around that time (no. 196) although it remained a stellar-appearing object of 15th magnitude. (Chiron passed through aphelion earlier this year, and I successfully imaged it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network just a few days later; to my knowledge, these are the first observations of the "new" return with a perihelion passage in 2046.) During his survey program Kowal also discovered several near-Earth asteroids, Jupiter's 13th and 14th known moons, and numerous supernovae, including one of the brightest such objects to appear during the 20th Century, Supernova 1972E in NGC 5253. I was able to join Kowal for one night at the 48-inch in February 1982; nothing unusual was found that particular night, but thanks to a night assistant who played cassette tapes of the BBC-TV series "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" (adapted from the writings of Douglas Adams) I first learned "The Answer" to "The Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything."

At the time of Kowal's discovery this comet had a perihelion distance of 1.52 AU and an orbital period of 6.4 years. It was missed at the unfavorable return in 1985 but was successfully recovered in 1991, and has subsequently been recovered at every return since then except in 2010 when it was very unfavorably placed for observation. During that time a couple of close approaches to Jupiter have decreased its perihelion distance, first to 1.4 AU and then to its present value of slightly under 1.1 AU, and have also shortened its orbital period to its present 5.7 years. Meanwhile, in 2003 astronomer Gary Kronk suggested that an apparent 10th-magnitude comet discovered in January 1973 by Leo Boethin in The Philippines (discoverer of Comet 85P/Boethin in 1975, which I observed during its subsequent return in 1986 (no. 89) but which apparently has since disintegrated and has been re-designated as Comet 85D) but seen by no one else was in fact Comet 104P/Kowal 2, and calculations soon confirmed this identity. The comet was over five months past perihelion at that time and was clearly undergoing an outburst; indeed, Boethin's report indicated a rapid fading.

I unsuccessfully looked for the comet one time during its 1991 return, but was able to follow it for two months during its 1998 return (no. 237), during which it reached 13th magnitude. I successfully observed it a couple of times during the mediocre return in 2016 (no. 596) when it again reached 13th magnitude, although it remained at a low altitude and was not easy to see. During its current return it was recovered on August 11, 2021 by the Pan-STARRS program in Hawaii and later that same day by ESA's Optical Ground Station at Tenerife in the Canary Islands, then by several other observers over the next couple of days. According to various reports I've read and images I've seen the comet remained very faint for some time after its recovery, but seems to have brightened quite rapidly within the recent past, and some recent images I've seen (including a pair I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory network) suggested it was now bright enough to attempt visually. On the evening of December 26 I successfully observed it as a diffuse, somewhat condensed object of 11th magnitude.

Comet 104P is in the evening sky (where it remains throughout the remainder of this apparition), presently located in far northeastern Aquarius and traveling towards the east-northeast at approximately one degree per day. It crosses into southern Pisces just before the end of the year, before crossing into Cetus a week later where it remains for the next six weeks (with the exception of a brief sojourn back into southeastern Pisces in late January, when it passes 10 arcminutes north of the star Alpha Piscium on the 27th); it then travels through Taurus, Orion, and Gemini where -- now heading almost directly eastward -- it remains until the latter part of April. After passing through perihelion in early January the comet is closest to Earth (0.64 AU) on January 28, and it seems reasonable to suspect the comet may brighten by perhaps a magnitude or so by around that time before starting to fade, and it may remain visually detectable until perhaps sometime in March. Since it has been known to undergo outbursts and other unusual behavior in the past it is conceivable that it may do so again during this return, so this predicted scenario could possibly be different from what really happens.

The comet undergoes another close approach to Jupiter (0.62 AU) in 2031, which decreases the perihelion distance further to slightly under 1.0 AU and shortens the orbital period to 5.5 years, values which will more-or-less remain unchanged through most of the rest of the 21st Century. These changes in its orbit will produce occasional close approaches to Earth, including one to 0.25 AU in 2039 and another to as close as 0.09 AU in 2049. Even if I'm still alive during those times I expect to have stopped visual comet observing long before then, so whatever additional observations of Comet 104P I am able to obtain this time around will almost certainly be my last.

The rapidly-concluding year of 2021 has seen some interesting developments for me, including my becoming a biological grandfather for the first time and my "semi-retirement" from visual comet observing after achieving my 500th separate comet. I face the approaching year of 2022 with some cautious optimism, both for myself personally and for the wider world at large, and I am presently working on a couple of projects that, possibly, could make a difference in things. I expect to continue my imaging efforts with the Las Cumbres Obsevatory network, and as I have done ever since I began my "semi-retirement" I expect to make the occasional visual observations of the brighter and more interesting comets for at least the near-term foreseeable future. Indeed, Comet Leonard C/2021 A1 (no. 707) has now become a naked-eye object for my friends in the southern hemisphere; poor weather and viewing geometry kept me from following it very much recently, although I did manage a decent observation -- low in my southwestern sky during dusk and bright moonlight -- a week ago. The incoming Comet PANSTARRS C/2021 O3 has the potential to become a bright object after its perihelion passage this coming April, although its brightness and appearance in the LCO images I've taken are not especially encouraging at this point. As in all things, though, we'll see what the future holds . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 December 27.09 UT, m1 = 11.0, 3.6' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

713. COMET LEMMON-PANSTARRS C/2021 F1 Perihelion: 2022 April 6.87, q = 0.995 AU

In general, as I continue to wind down my visual observation activities I am concentrating primarily upon the brighter and more easily observable comets, although I will still occasionally go after fainter comets -- especially if they are "interesting" in some way or other. Such is the case with this comet, as I feel a bit of a "connection" to it, since I played a role in its overall story -- a relatively minor role, to be sure, but a role nevertheless. And while it may very well end up being a "one-time wonder" on my overall comet tally, at least I was able to obtain an observation of it.

The comet was discovered on March 19, 2021, by the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona, and independently less than an hour later by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii. The discovery images, as well as follow-up images taken from these sites and elsewhere, all showed it as a completely asteroidal-appearing object of 21st magnitude even though it was found to be traveling in a distinctly long-period cometary orbit with a perihelion passage a little over a year in the future, and it was announced under the designation A/2021 F1.

After passing through conjunction with the sun in mid-October, the object began emerging into the morning sky towards the end of 2021. In early December Japanese amateur astronomer Hidetaka Sato reported that it was apparently beginning to exhibit cometary activity, and on the 10th I took a couple of images via the Las Cumbres Observatory network; to my eye, the question as to whether or not it could be considered "cometary" was somewhat inconclusive, although on the other hand it was clearly brighter than the ephemeris prediction for that time. Then, on January 28, 2022, I took an additional pair of images, and on these it was clearly cometary with a moderately bright and somewhat condensed coma. I reported this to my colleagues in the comet community, and other observers soon began reporting this as well, with most of them (including at least one visual observer) reporting that it was somewhere around 13th to 14th magnitude. Shortly thereafter, it was formally announced as a comet and named accordingly.

Due to weather (including a somewhat large winter snowstorm and some extremely cold temperatures for a few nights) and other considerations, it was a while before I was able to attempt a visual observation. I was finally able to do so on the morning of February 11, and I successfully detected the comet as a vague and diffuse object just fainter than magnitude 12 1/2. At that time it was traveling almost due eastward at 1 1/2 degrees per day and I could detect motion in as little as 10 minutes.

Images of Comet Lemmon-PANSTARRS I have taken via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: A "stack" of two 5-minute images taken from the LCO facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands on December 10, 2021. The comet is the faint, almost starlike object near the center. RIGHT: A single 5-minute image taken from the LCO facility at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii on January 28, 2022.

Images of Comet Lemmon-PANSTARRS I have taken via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: A "stack" of two 5-minute images taken from the LCO facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands on December 10, 2021. The comet is the faint, almost starlike object near the center. RIGHT: A single 5-minute image taken from the LCO facility at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii on January 28, 2022.

Comet Lemmon-PANSTARRS is traveling in a steeply-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 107 degrees) and has an approximate orbital period of 3000 years. At this writing (just before mid-February) it is at its closest approach to Earth (1.41 AU) and for the time being remains in the morning sky, being currently located in northern Cygnus some three degrees north of the bright star Deneb. Its continued rapid eastward motion -- which gradually curves more and more southward -- carries it through conjunction with the sun (53 degrees north of it) at the end of February, and during the first half of March it should be accessible in the evening sky (albeit at a fairly low altitude) as it travels through southeastern Andromeda. The comet's elongation drops below 30 degrees during the last week of March, and at the time of perihelion passage it will be located on the far side of the sun from Earth and unobservable. During the second half of April it traverses the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard the SOHO spacecraft, and by early June it begins emerging into the southern hemisphere's morning sky. Afterwards it continues traveling towards the south-southeast at approximately 45 arcminutes per day, and it enters southern circumpolar skies towards the end of August.

As is the case with any long-period comet, brightness predictions for Comet Lemmon-PANSTARRS are problematical. There is evidence that it may still be in the process of "turning on" and thus may still be brightening, although I would be surprised if it became any brighter than about 11th magnitude before it disappears into evening twilight. (If that is indeed the case, it will very likely be too faint to be detectable in the LASCO images during late April.) It may perhaps be near 12th magnitude when it becomes visible from the southern hemisphere during June, but will likely fade beyond visual range within another month.

It is unfortunate that Comet Lemmon-PANSTARRS is passing through perihelion at the time it does. Its orbit passes only 0.08 AU from Earth's orbit, and if it instead were to pass through perihelion around September 24 it would pass that distance from Earth itself a little over three weeks later. Based upon its present brightness it would be a naked-eye object of 5th or 6th magnitude, and would be near opposition and traveling towards the south-southwest at a rate that would briefly exceed 20 degrees per day.

A minor bit of personal trivia: with this comet 2022 becomes the 21st consecutive year during which at least one comet on my tally has passed through perihelion during the month of April. There are known inbound comets that I have a reasonable expectation of seeing that have April perihelion passages during each of the next two years as well, so provided that I remain active for at least that long this string should continue for at least a little while longer.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2022 February 11.49 UT, m1 = 12.7, 2.2' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

714. COMET 116P/WILD 4 Perihelion: 2022 July 16.91, q = 2.197 AU

Once again, a long-time "friend" makes an appearance on my lifetime comet tally, for what will almost certainly be the last time. This particular comet was discovered in 1990, and I observed it on that discovery return (no. 138) and on every return it has made since then; I discuss its overall history, and my history with it, in the "Countdown" entry for its 2009 return (no. 447). Since that time I observed it during its return in 2016 (no. 589), and although it struck me as being slightly fainter than what I expected, I nevertheless followed it for five months that time around.

As I pointed out in its "Countdown" entry, Comet P/Wild 4 can and has been imaged throughout its orbit, and accordingly can be considered as an "annual" comet and thus is not "recovered" in the traditional sense. The earliest reported observations of the current return were made on December 5, 2020 via the Steward Observatory's Bok Telescope located at Kitt Peak in Arizona, which is now being utilized by the Catalina Sky Survey. After being in conjunction with the sun in June 2021 the comet began emerging into the morning sky later last year, and recent images of it I've seen, as well as my own experience with it during previous returns, suggested it is now bright enough to attempt visually. On the evening of February 26, 2022 I successfully detected it as a small and somewhat condensed object slightly brighter than 13th magnitude.

The geometry of this year's return is almost identical to that in 2009, the respective perihelion dates being just two days apart. The comet was at opposition in mid-February and was nearest Earth (1.44 AU) just a couple of days before I first picked it up. It is currently located in western Leo a few degrees south of the "head" of that constellation and is traveling relatively slowly towards the west; it reaches its stationary point -- three degrees west of its present location -- at the end of March. After that it travels towards the east-southeast but remains in Leo for almost another four months, passing just over a degree north of the bright star Regulus on May 26. The comet is probably close to its peak brightness, although it should maintain something close to its present brightness for another couple of months or so before starting a gradual fading. In my present reduced level of observational activities I will probably only be making a handful of additional observations of it, at most.

There are no close approaches to Jupiter for almost another four decades, and with its present orbital period of almost exactly 6.5 years Comet Wild 4 will alternate between evening returns like the present one and morning returns like that of 2016 throughout that time. A handful of moderately close approaches to Jupiter during the latter decades of the 21st Century will introduce some changes to the comet's orbit, although none of these are especially dramatic. In any event, this year's return will almost certainly be my last, and I will leave observations at all these upcoming returns to observers of future generations.

The observations I am making at the present time are coming at a very difficult period of world affairs, primarily due to the invasion of Ukraine. I have friends and astronomical colleagues in Ukraine who are being adversely affected by these events, and I also have friends and astronomical colleagues in Russia who I have good reason to believe are just as opposed to this invasion as I am. (I have mentioned some of these individuals, on both sides, throughout various previous entries.) I can only hope that this entire horrible situation is resolved soon, and peacefully, and with dignity for all the innocent parties involved, so that we can get back to the task of building the peaceful world that I have devoted my entire career towards.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2022 February 27.14 UT, m1 = 12.8, 0.7' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

715. COMET ATLAS C/2019 T4 Perihelion: 2022 June 9.14, q = 4.242 AU

A distant large-q long-period comet joins my tally, a relatively rare occurence. This is the largest-q comet to enter my tally in 4 1/2 years, and of all the comets currently on my tally it has the 19th-largest perihelion distance; among long-period comets it has the 12th-largest perihelion distance.

The comet was discovered as long ago as October 9, 2019 by the ATLAS program based in Hawaii, at the time appearing as a relatively faint object of 19th-magnitude and -- at a heliocentric distance of 8.56 AU -- already exhibiting cometary activity. It was at opposition in late January 2021 and some reports I read and images I saw -- including some I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory network in February and March -- suggested it might be bright enough to attempt visually; I made a couple of attempts during that time frame but couldn't convince myself I was seeing it. (The fact that it was located between declinations of -35 degrees and -40 degrees, and was traveling through rich Milky Way star fields in Puppis, didn't help.) After being in conjunction with the sun last August it became accessible in the morning sky late last year, and various recent reports and images I've seen have all suggested that it has brightened further and is likely within visual range now. When I attempted it on the evening of April 2 I could easily detect it as a small and relatively condensed object of 13th magnitude.

Comet ATLAS just recently went through opposition and is currently at its closest approach to Earth (3.33 AU). At present it is located in southeastern Crater at a declination near -20 degrees, and is traveling slowly towards the north-northwest (passing half a degree east of the star Zeta Crateris on April 14), curving more directly northward until passing through its stationary point in early May and then crossing into Virgo in mid-June, where it remains for the next several months. The comet is probably as bright now as it is going to get, although since it is still a little over two months before perihelion passage it may remain close to its present brightness for perhaps another month or so before beginning a gradual fading; in any event, I will probably at most obtain just a small handful of additional observations. Conceivably, it may still be bright enough for visual observations as it approaches its next opposition in mid-May 2023 (when it will be located in northern Serpens Caput), although it will likely be quite faint, and in my present limited state of observational activity it is doubtful that I will attempt any such observations.

I made my initial observation of Comet ATLAS during a rare period of being "home alone" (with the exception of the cats), as Vickie and her father have been traveling out-of-State for a family wedding. On the larger world scale, I continue to grieve and be shocked by the senseless slaughter going on during the war in Ukraine, although this is probably not much different from the slaughter that has gone on during all the wars that have plagued humanity throughout its history. I had hoped that we were on a path away from that -- and I have tried to make my own contributions towards that end -- but, sometimes, I just have to shake my head . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2022 April 3.23 UT, m1 = 12.9, 0.5' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (April 24, 2022): When I made my initial observation of Comet ATLAS it was located fairly close to a star of similar brightness, which may have affected my brightness measurement. When I observed it again on the evening of April 21 it was in a "clean" location, and I was easily able to detect it as a relatively condensed object of 12th magnitude. I don't believe it has actually brightened during the interim, it's just that under the improved viewing circumstances I was able to get a better view of its true appearance. The remainder of the comet's apparition should still more-or-less follow the scenario I described above.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2022 April 22.18 UT, m1 = 12.2, 0.8' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (April 19, 2023): I continued to follow Comet ATLAS on an occasional basis for another couple of months, before the summer monsoon started to curtail observations and the comet started to get low in the western evening sky. For a while it maintained a brightness near 12th magnitude, although it started to fade somewhat by the time I stopped following it in late June. After conjunction with the sun in October it started to emerge into the morning sky by the latter weeks of 2022, and has been followed by various observers around the world since that time. Numerous recent reports I've read and images I've seen have suggested that it is still bright enough for visual observations, but as I indicated above I've had no real plans to observe it. However, the current visual comet activity in the nighttime sky has slowed down considerably since earlier this year, and in an effort to ensure that I have something to observe over the near-term future I decided it might be worthwhile to give this comet a try, and this morning I successfully detected it as a small, moderately condensed object of 13th magnitude. Incidentally, with this observation Comet ATLAS becomes the 60th comet on my tally that I have followed in excess of one year, which is just over 8% of all the comets on the tally.

Comet ATLAS is currently near its closest approach to Earth (4.14 AU) of the current viewing season, and will pass through opposition shortly before mid-May. It is located in northern Serpens Caput two degrees northwest of the star Beta Serpentis and is traveling towards the north-northwest at approximately 10 arcminutes per day, although it gradually slows down and curves more directly westward as it approaches its stationary point in early July. It will probably maintain something close to its present brightness for a few more weeks, although before too long it will likely begin fading. In any event, I will probably only observe it a handful of additional times, and meanwhile within the next two to three months the comet activity should start picking up again.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2023 April 19.41 UT, m1 = 12.9, 0.7' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

716. COMET ATLAS C/2021 P4 Perihelion: 2022 July 30.37, q = 1.080 AU

Thus far, every comet that I have added to my tally during 2022 has been a rather dim and nondescript object, and this one continues that same basic trend. Like the previous comet, this one was found by the ATLAS survey based in Hawaii, the discovery having taken place on August 10, 2021, at which time it was a dim 19th-magnitude object traveling slowly through rich Milky Way star fields a few degrees south of the center of the "W" of Cassiopeia. Traveling in a moderately steeply-inclined direct orbit (inclination 56 degrees) with an approximate period of 5000 years, the comet has remained in that same basic part of the sky ever since, going through opposition in late September and being currently located low in the northwestern sky after dusk. It has brightened steadily since its discovery, and recent images I've seen have suggested that it might now be bright enough for visual observations; when I made my first attempt, on the evening of April 21, I successfully detected it as a small and relatively condensed object slightly fainter than 13th magnitude.

At present Comet ATLAS is located at an elongation of 47 degrees, in southeastern Cassiopeia about five degrees east-northeast of the "Double Cluster" (NGC 869 and 884), and traveling essentially eastward at approximately 40 arcminutes per day; it crosses into southern Camelopardalis shortly before the end of April. Over the subsequent weeks it gradually begins curving southward, while the elongation drops below 40 degrees in late May; it crosses into Lynx in early June and meanwhile the elongation drops below 30 degrees just before the end of that month. At the time of perihelion passage the comet is on the far side of the sun from Earth, being at an elongation of just 20 degrees; it is in conjunction with the sun (27 degrees south of it) around the time of the September equinox, and thereafter remains at a fairly small elongation through the end of 2022, although it enters southern circumpolar skies by the end of November.

The comet should continue brightening slowly as it approaches perihelion, and may be close to 12th magnitude by the time it starts disappearing into the dusk during the latter part of May; due to its already low placement in the northwestern evening sky and its gradually decreasing elongation I will at most probably only obtain one or two additional observations of it before that time. It will probably be too faint for visual observations by the time it becomes accessible for observers in the southern hemisphere late this year.

As was the case with Comet Lemmon-PANSTARRS C/2021 F1 (no. 713), Comet ATLAS' orbit comes quite close to that of Earth (minimum distance 0.09 AU), but the comet itself passes through perihelion at an unfavorable time of the year. If it were instead to pass through perihelion during early March, it would be passing that minimum distance from Earth right around that same time, and would be near opposition and traveling towards the south-southwest at a rate that would briefly reach about 12 degrees per day. Based upon its present brightness, it would likely be a naked-eye object near 4th magnitude as it made its passage by Earth. We don't win 'em all . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2022 April 22.12 UT, m1 = 13.3, 0.4' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

717. COMET PANSTARRS C/2021 O3 Perihelion: 2022 April 21.05, q = 0.287 AU

Throughout all the years I have been engaged in comet observing, it happens from time to time that an inbound comet -- especially if it has a small perihelion distance -- exhibits the potential for putting on a bright, perhaps naked-eye, display. While it does happen on occasion that such a comet will meet, possibly even exceed, such expectations -- case in point being Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 (no. 676) two years ago -- more often than not such comets fail to live up to these initial expectations, and in some cases -- for example, Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4 (no. 673), which also appeared two years ago -- have even been known to disintegrate altogether as they have approached or passed through perihelion. This comet, discovered by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii on July 26, 2021, certainly ranks among those that have failed to live up to their initial potential for a bright display.

Some of the reported observations after its discovery suggested the comet was around 19th magnitude, which is actually somewhat bright for a Pan-STARRS-discovered comet, and in turn suggested it was bright enough for me to attempt images with the Las Cumbres Observatory (LCO) network. I was indeed able to obtain images of it on July 30 and again on August 1, and my astrometric measurements from these were included on the discovery announcement that was issued on that latter date. The initial orbital calculations indicated that the comet was located about 4.3 AU from the sun, and would be passing perihelion slightly less than nine months later at the small heliocentric distance of 0.3 AU. The post-perihelion viewing geometry would be reasonably favorable for the northern hemisphere, and, indeed, there appeared to be some similarities to the apparition of Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3; while a display as good as the one that object produced would probably be too much to hope for, the prospects for some kind of decent display appeared to be at least somewhat reasonable.

It soon became clear, however, that there were some significant differences between Comet NEOWISE and Comet PANSTARRS. Unlike Comet NEOWISE, Comet PANSTARRS appears to be a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud, and such comets often tend to under-perform as they approach and pass through perihelion. Indeed, Comet PANSTARRS brightened rather slowly during the months following its discovery, and was no brighter than about 17th magnitude when I obtained my most recent LCO images in early December. It was still only 15th to 16th magnitude when the final observations were reported as it began entering evening twilight in early February 2022.

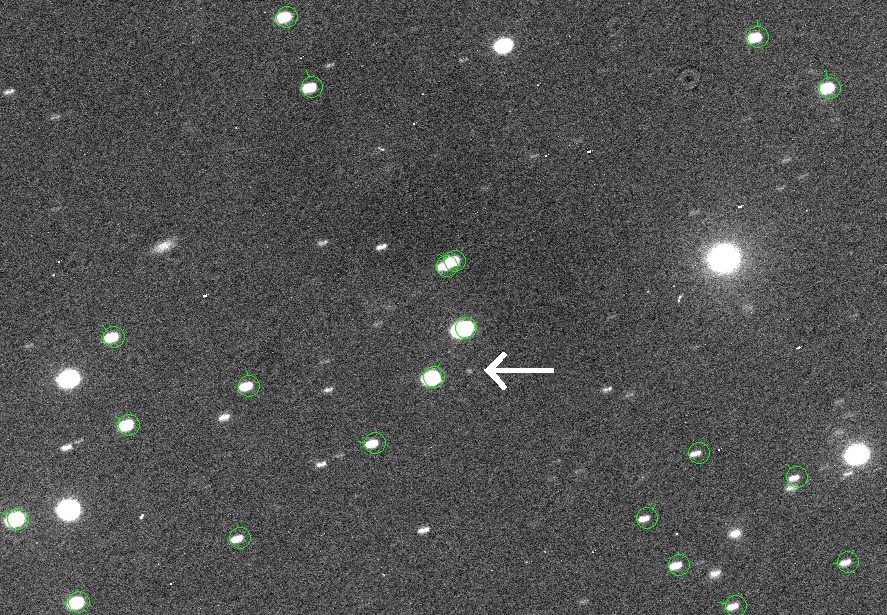

Images of Comet PANSTARRS I obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: July 30, 2021, via the LCO facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands. This was while the comet was still on the Possible Comet Confirmation Page (PCCP), and my astrometric measurements were utilized and published in its discovery announcement. The green circles are reference stars identified by the astrometry reduction program "Astrometrica." RIGHT: December 3, 2021, via the LCO facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas. The comet is the faint, diffuse object near the center.

Images of Comet PANSTARRS I obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: July 30, 2021, via the LCO facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands. This was while the comet was still on the Possible Comet Confirmation Page (PCCP), and my astrometric measurements were utilized and published in its discovery announcement. The green circles are reference stars identified by the astrometry reduction program "Astrometrica." RIGHT: December 3, 2021, via the LCO facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas. The comet is the faint, diffuse object near the center.

After entering twilight Comet PANSTARRS spent the next three months on the far side of the sun from Earth and accordingly hidden in sunlight. During the latter part of March it spent a week and a half in the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO and, somewhat surprisingly, was bright enough to be detected, being around 9th magnitude, and suggesting that perhaps it might indeed put on some kind of respectable show after all. After the first week of April it became detectable in images taken with the Solar Wind ANisotropy (SWAN) ultraviolet telescope aboard SOHO, with these initially suggesting it might be around 8th magnitude. Unfortunately, however, it seemed to fade afterwards, and during the latter part of April -- around which time its elongation was near 16 to 17 degrees -- observers in the southern hemisphere had mixed results in detecting it from the ground, with even the most successful of these efforts indicating that it wasn't any brighter than 9th or 10th magnitude. Since the comet was passing through perihelion around that time the general consensus among comet astronomers was that it was likely disintegrating.

As Comet PANSTARRS -- or whatever might be left of it -- receded from perihelion it would be located between the earth and the sun, reaching a maximum phase angle of 136 degrees at the very end of April and being at a minimum distance from Earth of 0.60 AU on May 8. Starting at the beginning of May it would be rapidly climbing out of twilight into the northern hemisphere's evening sky, and various observers began reporting that it was definitely visible on images and thus had not disintegrated -- at least, not entirely. It was, however, very diffuse and uncondensed in appearance, and much fainter than what had been predicted for this time: most reports indicated a brightness anywhere between 12th and 15th magnitude.

Incidentally, this is the third time that I have added a comet to my lifetime tally during a total lunar eclipse. During the eclipse on the evening of November 8, 2003 I added Comet Tabur C/2003 T3 (no. 344), and I added the 2015 return of Comet 10P/Tempel 2 (no. 584) during the eclipse on the evening of September 27 of that year. (That comet returned again last year, but was poorly placed for observation -- especially from the northern hemisphere --and the one attempt I made for it -- almost five months after perihelion passage -- was unsuccessful.)

Comet PANSTARRS is presently in northern circumpolar skies, located in Camelopardalis near a declination of +72 degrees. It is traveling towards the north-northeast, presently at somewhat over two degrees per day although slowing down as it continues pulling away from Earth, and reaches a maximum northerly declination of +81.6 degrees on May 28 before turning towards the south-southeast. It passes one degree northeast of the former pole star Thuban (Alpha Draconis) on June 22 and exits northern circumpolar skies in early July. Meanwhile, the disintegration process that apparently began during the comet's approach to perihelion will likely continue and it will probably fade while growing more and more diffuse, and I suspect it will not remain visually detectable for very long. Indeed, it is entirely possible that my "eclipse" observation on May 15 will remain my only visual observation of this comet.

So, once again a potentially bright cometary display fails to materialize. I hope that I get to see at least one more decently bright comet before my probable "retirement" in a little over two year's time; one recently-discovered long-period comet, Comet ZTF C/2022 E3, may become dimly visible to the naked eye when it passes somewhat close to Earth next February, and while I don't expect either of these to become especially bright, the Halley-type comets 12P/Pons-Brooks and 13P/Olbers that are returning in 2024 should at least become bright enough to be worthwhile. There is always the possibility, of course, that an as-yet-undiscovered inbound comet could become bright during the near- to intermediate term future, but about all we can do is wait and see what the heavens have in store for us.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2022 May 16.15 UT, m1 = 12.9, 1.2' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 229x; during total lunar eclipse)

718. COMET 45P/HONDA-MRKOS-PAJDUSAKOVA Perihelion: 2022 April 26.95, q = 0.557 AU

This comet became just the third periodic comet I ever observed when I followed it for 3 1/2 weeks during its 1974 return (no. 13), at which time I was in my junior year of high school. It has been a semi-regular guest on my lifetime comet tally ever since, and I discuss its overall observational history (including how it obtained its rather cumbersome name), and my own history with it, in its "Countdown" entry when I observed it in 2011 (no. 490). During that return it passed only 0.060 AU from Earth -- at present, the 6th-closest approach to Earth of any comet on my tally -- and reached 7th magnitude.

As I pointed out in its "Countdown" entry, during its subsequent return (perihelion at the very end of 2016) Comet 45P passed 0.083 AU from Earth the following February -- at this time, the 11th-closest approach to Earth of any comet on my tally. I first picked it up in late November 2016 (no. 609) and it became almost as bright as magnitude 6.5 as it passed through perihelion, although this took place when it was low in the southwestern sky after dusk, and it shortly thereafter disappeared into twilight. After going through inferior conjunction with the sun in late January 2017 it re-emerged into the morning sky in early February, and appeared as a large, diffuse object of 8th magnitude as it made its passage by Earth shortly before the middle of that month. Perhaps a little bit surprisingly -- since historically the comet usually brightens and fades very rapidly -- I was able to follow it until the end of March.

The current return is the 7th at which I have observed Comet 45P, and it becomes only the fourth periodic comet that I have observed on that many returns. In contrast to the two previous returns, on the current one Comet 45P remains far from Earth and the viewing geometry is distinctly unfavorable, and in all honesty I never expected to look for it, let alone observe it. It was recovered on April 16, 2022 when Chinese researcher Zhijian Xu noticed it crossing the field-of-view of the LASCO C2 coronagraph aboard SOHO, and as it exited C2 a few days later it was visible in the C3 coronagraph. The comet remained in the C3 field-of-view through almost the rest of April and towards the end of that time (when it was close to perihelion passage) it appeared at a somewhat unexpectedly bright 7th magnitude and exhibited a short tail.

The first ground-based images were obtained on May 10 (evening of May 9, local time) by amateur astronomer Mike Olason in Arizona; its elongation from the sun at the time was only 17 degrees, and it appeared as a rather condensed object a bit brighter than 7th magnitude -- distinctly brighter than expected. (Around that same time it was also near its closest to Earth, 1.51 AU.) Olason, and subsequently other observers, continued to image it on subsequent nights as its elongation slowly increased, and since its brightness seemed to be holding steady -- exhibiting perhaps only a small decrease -- it began to look like visual observations might be possible. Due to smoke from a large forest fire burning in southwestern New Mexico I was unable to make any meaningful attempts for several nights, but finally on the evening of May 21 I had decent conditions, and from a site a short drive from my residence (since I don't have a clear horizon in that direction) I successfully detected it using a small portable telescope that I had purchased four years ago. The comet's elongation at the time was 25 degrees and it was only 5 degrees above the horizon (in astronomical twilight) when I observed it; it appeared as a moderately condensed object slightly fainter than magnitude 7 1/2.

At present Comet 45P is located in far eastern Taurus a little over two degrees east of the star 132 Tauri, and is traveling due eastward at 1 1/2 degrees per day (and accordingly it soon crosses into Gemini, passing half a degree north of the star cluster M35 on May 26 and 20 arcminutes south of the star Epsilon Geminorum five days later); its elongation is increasing by roughly half a degree per day and reaches 30 degrees at the beginning of June. It slows down over the coming weeks as it continues receding from the sun and Earth, and it reaches a maximum elongation of 35.5 degrees in late June before beginning a gradual disappearance back into evening twilight. As far as its brightness is concerned, as I mentioned above it is distinctly much brighter than expected -- indeed, based upon its historical performance it shouldn't be any brighter than 11th or 12th magnitude at present -- and thus whatever future observations I might make depend upon how long it maintains its present brightness. If, as I suspect might happen, it starts to fade within the near future, the continued poor viewing geometry will likely mean that I will not attempt to see it again.

I pointed out in its "Countdown" entry that Comet 45P's next return, in 2027 (perihelion late August), is moderately favorable; it passes 0.54 AU while inbound to perihelion, and even based upon its historical brightness behavior it might reach 8th or 9th magnitude (and could be even brighter if its present behavior holds). However, this is well after what I have been considering as my expected "retirement" from visual observing in 2024, and while the adage of "never say 'never!'" might apply, the closer I get to that time the more I believe I will hold to that timeframe. It is thus reasonably likely that the one observation I made of Comet 45P a few nights ago will be my final observation of it -- but since I never expected to see this comet this time around anyway, I am quite glad I was able to get that observation.

I can't help noticing some interesting connections between this comet and my partner Vickie. For one thing, the brightest comet discovered by one of its co-discoverers, Antonin Mrkos -- Comet Mrkos 1957d -- was a conspicuous naked-eye object in the sky when Vickie was born. What I find most interesting is that Vickie and I began seeing each other in February 2017 during Comet 45P's previous return -- indeed, I observed it the very next morning after returning home from our first date. It's almost as if it was deliberately bright this time around in order to check in on us and see how we're doing. I'm happy to show it that we're doing just fine; in fact, Vickie assisted me in this recent observation. If I have anything to say about it, she and I will continue to do fine for as long as . . . whatever the future holds . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2022 May 22.14 UT, m1 = 7.7, 4.0' coma, DC = 5-6 (10 cm SCT, 40x)

719. COMET 22P/KOPFF Perihelion: 2022 March 18.13, q = 1.552 AU

Yet again, an "old friend," with which I share some interesting memories, shows up on my tally for what will probably be -- or, conceivably, may not be -- the last time. Like quite a few other "old friend" periodic comets, I observed it during the course of "Countdown," and I discuss its observational history, and my own history with it, in its "Countdown" entry for its 2009 return (no. 448). Since that time it returned under somewhat mediocre geometrical conditions in 2015, but I nevertheless managed to follow it for four months then (no. 572) and it reached a peak brightness slightly brighter than 13th magnitude.

Comet P/Kopff's current return is the 6th return of it that I have observed. It was recovered as long ago as January 25, 2020, by the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona (although some time later the Zwicky Transient Facility survey in California reported observations from two days earlier). As I indicated in its "Countdown" entry, this return is a rather mediocre one; it was in conjunction with the sun last October, and since the beginning of this year has been slowly emerging into the morning sky, and even at perihelion passage its elongation was only 46 degrees. It has also been located south of the sun throughout this time, which means that observations were pretty much restricted to the southern hemisphere, and I have seen occasional images and reports from observers there that indicated its brightness was around 12th magnitude. Even though for the time being it remains low in the southeastern sky before dawn, it has finally become accessible from the northern hemisphere, and some recent images I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory network indicated it was still bright enough to be worth attempting visually. On the morning of May 28 I successfully detected it as a small and slightly condensed object of 13th magnitude -- a bit fainter than what I expected, but nevertheless "there." (As an extra bonus, the planets Mars and Jupiter were in a somewhat close conjunction with each other just over three degrees from the comet's location.)

Comet P/Kopff is currently located in southern Pisces two degrees northeast of the star 29 Piscium and is traveling towards the east-northeast at half a degree per day. It passes just over a degree south of Jupiter on June 5 and then crosses into Cetus five days later, although it remains close to the border between northern Cetus and southeastern Pisces for the next few months; it goes through its stationary point shortly after mid-August and is at opposition in early October. Although still approaching Earth -- minimum distance 1.39 AU in mid-September -- since it is already over two months past perihelion and fading and also remains low in the southeast before dawn for at least a few more weeks, I don't expect to make many more observations, probably no more than one or two.

As I have mentioned in numerous previous entries I am thinking seriously of "retiring" from visual observing in 2024, and thus any additional observations I might make of Comet P/Kopff this time around would likely be my last ones of it. However, as I also indicated in its "Countdown" entry, between now and the next return the comet passes close to Jupiter (0.44 AU in June 2026) which among other things will drop its perihelion distance down to 1.32 AU. At that next return (perihelion late June 2028) it passes only 0.35 AU from Earth in mid-July, and while the peak brightness of 4th or 5th magnitude that I mention in its entry may be a bit optimistic, a relatively bright appearance -- perhaps 6th or 7th magnitude -- would still seem to be a reasonable expectation. Whenever I have discussed my "retirement" I have also included the caveat that I reserve to myself the right to "come out of retirement" if something bright or interesting comes along, so while any crystal ball I might have does not extend that far into the future, it is at least conceivable that I might see this comet again.

For what it's worth, another close approach to Jupiter (0.67 AU) in 2038 will contribute toward dropping P/Kopff's perihelion distance down to 1.16 AU, and it passes only 0.18 AU from Earth in July 2095. Regardless of what might remain in my future I believe I can say with some confidence that I will not be seeing this comet then . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2022 May 28.43 UT, m1 = 12.8, 0.8' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

720. COMET ZTF C/2020 V2 Perihelion: 2023 May 8.56, q = 2.228 AU

I have now added exactly 100 comets to my tally since I recommenced posting my tally entries five years ago (although it's fair to note that three of these comets are retroactive entries of objects I had previously observed as "asteroids"). It has been a fairly eventful five years, and I am happy to say that my overall frame of mind is quite a bit better than it was at that time (as was reflected in the personal statement I posted when I began this new series of entries). A significant part of this is due to my partner Vickie, whom I had actually started seeing shortly before I wrote that statement, and who moved in with me in early 2019 (and whose father joined us a year and a half later). Some of the other major events of these past five years include a trip to observe the total solar eclipse in August 2017 from Corvallis, Oregon (where my younger son Tyler was living at the time) and a three-week-long visit to Australia in early 2019 for a teaching gig with the International Space University (and also to visit my older son Zachary, who was living in Adelaide at the time). I became a biological grandfather for the first time with the birth (to Tyler) of my grandson Ethan 15 months ago, and meanwhile in mid-2018 I underwent a period of hospitalization that reflects the health issues I have been facing these past few years and that, as I have discussed in several previous entries, changed "retirement" from visual observing from the hypothetical possibility I once discussed into something that will likely happen for real within the not-too-distant future. There have also been numerous happenings on the national and international scale, including the global COVID-19 pandemic two years ago that altered the lives of just about all of us.

This "100th comet" was discovered on November 2, 2020 by the Zwicky Transient Facility suvey program that utilizes the 1.2-meter (48-inch) Oschin Schmidt Telescope at Palomar Observatory in California (although pre-discovery images taken elsewhere extending back to April 2020 were later identified). This is the same survey program that discovered Comet Palomar C/2020 T2 (no. 697) and some earlier comets also named "Palomar," however beginning with this comet the IAU's Working Group on Small Body Nomenclature has assigned the name "ZTF" to comets discovered by this program. Since that time there have been four additional "ZTF" comets discovered, as well as Comet 414P/STEREO P/2021 A3 (no. 693) which was re-discovered by this program but did not have the name "ZTF" added to it. One of these, C/2021 E3, passed through perihelion earlier this month and is presently in southern circumpolar skies near 9th or 10th magnitude, and unfortunately it does not appear I will ever be able to observe it. Meanwhile, the most recent ZTF comet discovery, C/2022 E3, passes 0.28 AU from Earth next February (and will be traveling through northern circumpolar skies at that time), and may become visible to the unaided eye.

This Comet ZTF is traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 132 degrees), and appears to be a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud. At the time of its discovery it was located at heliocentric and geocentric distances of 8.7 and 9.4 AU, respectively, and was a dim object of 19th magnitude that appeared only barely non-stellar in images. It brightened slowly over the subsequent months as it approached the inner solar system, being at opposition near the end of March 2021 and in conjunction with the sun (36 degrees north of it) in late September. During the latter part of 2021 it began emerging into the morning sky en route to its next opposition shortly after mid-March 2022, and in late January I took some images of it via the Las Cumbres Observatory network, which suggested it might be worth visual attempts in the not-too-distant future. Since it still didn't seem especially bright, in my current state of reduced activity I didn't assign a high priority to it, and thus never quite got around to looking for it, however around late May some images I saw and even reports of visual observations indicated that it might now be worthwhile to attempt once the full moon had exited from the mid-June sky. Since we seem to be experiencing an early onset of monsoon season here in New Mexico -- which, since we are now under severe drought conditions and extreme fire warnings, is actually very welcome in these parts -- I had to wait a while for some clear skies, but during a brief respite from the rains on the evening of June 18 I successfully observed the comet as a small and condensed object of 13th magnitude.

The comet is presently in the northwestern evening sky, in western Ursa Major some two degrees north of the star Phi Ursae Majoris and, being currently at its stationary point, now begins traveling slowly towards the south-southeast. It is in conjunction with the sun (41 degrees north of it) shortly after mid-August and begins emerging into the morning sky within the next one to two months thereafter, still in western Ursa Major and now traveling towards the northeast. In late October it enters the "bowl" of the Big Dipper and passes just half a degree east of the star Dubhe (Alpha Ursae Majoris, the northwestern star of the "bowl") in early November before passing through its stationary point shortly after the middle of that month. For the next three months the comet travels through northern circumpolar skies, reaching a peak northerly declination of +85.9 degrees in late December (at which time it also passes through opposition). In January 2023 it is in Cassiopeia, traveling through the eastern part of the "W" of that constellation and passing 20 arcminutes east of the star Delta Cassiopeiae late that month at the same time it is at its other stationary point. Afterwards it travels toward the south-southeast, crossing into western Perseus in early February and into Andromeda a week later, remaining within that constellation until shortly after mid-March when it crosses into Triangulum. Before much longer the comet disappears into evening twilight, being in conjunction with the sun in late April shortly before its perihelion passage in early May.

While it is always a bit problematical to make predictions of a long-period comet's brightness, based upon its present brightness the comet should be at least 11th magnitude, possibly 10th, throughout most of this time. It is (temporarily) nearest Earth (2.06 AU) in early January.

Comet ZTF begins re-emerging into the morning sky during the latter part of June, being located in eastern Aries, and since it is south of the sun it is initially easier seen from the southern hemisphere. It is traveling in a general southerly direction, and passes through its stationary point in mid-July at the same time it is crossing into Cetus. For the next five months it travels southwestward through that constellation, then through Eridanus, Fornax, Sculptor, Phoenix, and Grus, being closest to Earth (1.86 AU) in mid-September, at opposition in early October (passing 15 arcminutes southeast of the bright galaxy NGC 300 on October 14), and at its farthest south point (declination -43.1 degrees) shortly after mid-November. It passes through its stationary point in late December and disappears into evening twilight in January 2024 before its next conjunction with the sun (39 degrees south of it) in mid-March. The comet should still be 10th to 11th magnitude throughout the first few weeks of this viewing season, but will likely start to fade fairly rapidly after opposition and be lost to visual observations by around the end of 2023.

It would appear, then, that -- provided my body and other life circumstances cooperate -- I will have this erstwhile "100th comet" around for a while, although I don't expect anything bright or dramatic from it and I will probably not be observing it all that often. I do not expect that there will be a second "100th comet" and, as I've indicated in previous entries, except for possible bright comets that might potentially and briefly bring me "out of retirement," I will likely not even be observing comets in five years' time. In the wider view, while as I indicated above my overall personal frame of mind is one of peace and quiet contentment, I am nevertheless still experiencing a "crisis of conscience," so to speak, due to various national and international events (some of which I have discussed in previous entries). In part because of this, for the past several months I have been taking an extended break from primary Earthrise activities, and have been pursuing endeavors that, at most, are only peripherally related to Earthrise. If and when I ever return to activities more directly related to Earthrise, these will likely focus on efforts to identify and support younger people who can continue on with the Earthrise mission. I still want to believe that this is a worthwhile effort . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2022 June 19.16 UT, m1 = 13.0, 0.6' coma, DC = 6 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (October 28, 2022): Due largely to the early onset of our annual monsoon season here in southern New Mexico, I was only able to obtain one additional observation of this comet before it became too low in my northwestern evening sky to observe. After its conjunction with the sun in August the comet began emerging into my northeastern morning sky by the latter part of September, however poor weather and moonlight prevented me from attempting any observations of it for the next few weeks. Finally, on the morning of October 26 I was able to observe it as a small and relatively condensed object of 11th magnitude; its coma exhibited a slightly non-spherical "teardrop" shape that is consistent with recent images I have seen.

The comet is presently located between the "pointer" stars (Alpha and Beta Ursae Majoris) in the Big Dipper, and is traveling towards the north-northeast at a little over a quarter of a degree per day. Its future motion is described in the scenario above, and since its present brightness appears to be consistent with that scenario the next several months should proceed more or less as expected.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2022 October 26.45 UT, m1 = 11.1, 1.2' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (June 28, 2023): To my eyes, Comet ZTF reached a peak brightness near 10th magnitude in mid-December 2022, then slowly faded by about a half-magnitude or so by the time I stopped following it in the northwestern evening sky three months later. After conjunction with the sun in late April the comet has started emerging into the morning sky, although as I mentioned above it has been better placed from the southern hemisphere. On the morning of June 28 I successfully picked it up as a diffuse, moderately condensed object of 11th magnitude; it was a bit more difficult to see than that brightness might suggest, since I not only had to contend with low altitude, zodiacal light and twilight, but also some inopportunely-placed clouds as well as the trees that are in that direction from my observing site.

Comet ZTF is currently located in southeastern Aries four degrees southeast of the star Rho Arietis and is traveling towards the south-southeast at 15 arcminutes per day. The viewing scenario for the upcoming few months should more-or-less follow what I described above. Although the comet does become better placed for observations within the relatively near future, the imminent start of our annual summer monsoon season will probably keep me from observing it very often for the next few weeks; on the other hand, while I probably won't be getting many observations of it, I should be able to follow it for at least another three or four months.

With this observation Comet ZTF becomes the 61st comet on my tally that I have followed in excess of one year. If I stick to the "retirement" timeframe of the end of 2024 that I have often discussed in these pages this may well be the last comet with which I achieve that milestone. Among the other comets already on my tally as well as upcoming known ones there aren't any -- with one possible exception -- that I have any real expectations of being able to follow for a full year or more. But, we'll see what happens . . .

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2023 June 28.43 UT, m1 = 11.1, 1.5' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x; low altitude, twilight)

<-- Previous

Next -->

BACK to Comet Resource Center