TALLY ENTRIES 631-640

A long-time acquaintance stops by for another visit. This comet was originally discovered as long ago as December 1911 by Alexandre Schaumasse, who observed from Nice Observatory in France. It was the first of three comets (the other two being long-period objects) that he discovered from Nice during the decade of the 1910s, a period of time during which he also served with the French Army during World War I and was severely injured. The comet was found to have an orbital period of close to 8 years (presently, 8.25 years) and while it has been recovered on most returns since its discovery, its perihelion distance of close to 1 AU means that on some returns it has remained on the far side of the sun for months at a time, and has gone unrecovered. On the other hand, on other returns it can become quite well placed for observation; in 1952 it passed 0.29 AU from Earth and at the same time apparently experienced an outburst of some kind, and for a while was as bright as 5th magnitude. The present return is the 11th (including its discovery return) at which it has been observed.

My personal history with Comet P/Schaumasse dates back to its 1984 return (no. 76), during the period of time when I was working with the Deep Space Network at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and was observing regularly with the experienced comet observer Charles Morris (who also worked at JPL). I followed the comet for 3 1/2 months during that return; when near perihelion in early December of that year it reached a peak brightness of magnitude 9 1/2 and I could faintly detect it with binoculars.

During the early 1980s when I was in the U.S. Navy and stationed in southern California, Mark was in the U.S. Air Force and stationed at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, and I would get to see him when I returned to New Mexico on leave. While I could not have known it at the time, I saw Mark for the very last time in early January 1982, shortly before his enlistment in the Air Force was up and he returned to North Dakota; it is only fitting that on that final occasion we observed a comet together, Comet Bowell 1980b (no. 46).

I next observed P/Schaumasse on its return in 1993 (no. 174), during which it passed 0.55 AU from Earth and reached a peak brightness of 9th magnitude. That return came during the period of time during which it became necessary for me to leave my job at what is now the New Mexico Museum of Space History and during which I began to develop and build what is now the Earthrise Institute. P/Schaumasse next returned in early 2001 (no. 288), a somewhat mediocre return during which it got no brighter than 11th magnitude; nothing really dramatic happened in my life during that return, although I obtained my final observation just before departing for Zimbabwe for the June 21 total solar eclipse, and of course there were events that happened on a national and international scale later that year that dramatically affected the directions in which I eventually took Earthrise.

The comet was badly placed for observation at its return in 2009, and it was not recovered. On its present return it was recovered on July 24, 2017 by Jean-Gabriel Bosch and Alain Maury from the Observatoire de la Cote d'Azur's San Pedro facility in Chile's Atacama Desert, as a rather faint object of 19th magnitude. After one unsuccessful attempt in early October I successfully picked it up during my first attempt of the current dark run, on the morning of October 21; it appeared as a vague, diffuse object of 13th magnitude.

The current return is slightly inferior in quality to that of 1984, and similar to that of 2001 (with the exception that that was an evening-sky return). The comet remains in the morning sky throughout this return, and in fact remains near a constant elongation between 55 and 60 degrees for the next two months before this gradually increases. It is presently located in central Leo approximately eight degrees east of the bright star Regulus (and about 14 degrees east of the previous comet which, curiously, passes through perihelion only 19 hours before this one does) and is traveling towards the east-southeast at one degree per day. It crosses into northwestern Virgo in early November and spends the rest of 2017 traveling through that constellation. Just after perihelion passage it spends the next few days traveling through the southern section of the Virgo galaxy cluster, and it is nearest Earth (1.46 AU) on November 21. In early January 2018 Comet P/Schaumasse crosses into western Libra and spends the next month traveling across that constellation before crossing into northern Scorpius in early February and then into Ophiuchus shortly after the middle of that month, where it remains for the next 3 1/2 months.

Based upon the brightnesses I have observed during previous returns, I expect P/Schaumasse to reach a peak brightness between 10th and 11th magnitude during the second half of November, perhaps extending into early December. After that it should begin fading and diffusing out, and I will probably lose it in late January or early February.

Unlike what happened during some of the earlier returns of this comet, I don't seem to have too much in the way of dramatic events in my life happening at this time -- at least, not yet, anyway -- although as I continue the healing process that I discussed in my July 6 personal statement I am starting to see some potential future activities for Earthrise beginning to coalesce in my mind, and I may have something to write about in that regard before too much longer; stay tuned! Meanwhile, some unfortunate life circumstances have forced my younger son Tyler to relocate from Oregon back to New Mexico for at least the near-term foreseeable future; he arrived back here just a week ago, and most unfortunately experienced a rather severe car accident while en route (although, fortunately, he walked away from it with only minor injuries).

P/Schaumasse's next return, in 2026 (perihelion early January) is a distinctly favorable one, similar to that in 1993, with a minimum separation from Earth of 0.59 AU. This is somewhat after the "retirement" timetable I describe in my accompanying statement to "Continuing with Comets," although how closely I will actually stick to that timetable, and, indeed, what I might actually mean by "retirement," are things that remain to be seen. It occurs to me, though, that, given the association I have in my mind between Mark and this comet, and given that Mark was with me at the very beginning of my comet-observing "career," perhaps it might be appropriate to close out that "career" with this comet. Time will tell . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2017 October 21.46 UT, m1 = 12.8, 1.6' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

632. COMET PANSTARRS C/2015 V1 Perihelion: 2017 December 17.74, q = 4.267 AU

During the time that I have been preparing this entry and the above entry, one of the most exciting discoveries in the entire history of solar system astronomy has been unfolding. On October 18 the Pan-STARRS program in Hawaii discovered a fast-moving object of about 20th magnitude, and over the course of the next couple of days additional observations indicated that it was traveling in an extremely elongated orbit and had passed perihelion at a very small perihelion distance (initially reported as about 0.15 AU, now more firmly established as 0.25 AU) over a month earlier; it was then placed on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page. When I saw the object's listing on the PCCP on the 21st it seemed very strange that a comet as apparently instrinsically faint as this one seemed to be could have survived perihelion passage at such a small distance from the sun, and I wondered if perhaps there might be a dim outer coma attached to it that would make it brighter intrinsically and would be detectable visually; this occurrence is rare, but I have noticed it in a handful of previous comets. I made an attempt for it that evening, but didn't see anything.

On the 24th the Minor Planet Center formally announced the Pan-STARRS discovery as a comet under the designation C/2017 U1. Attention was called to the fact that all orbital solutions indicated a strongly hyperbolic orbit with an eccentricity near 1.2 which, if confirmed, can only mean one thing: this object came from interstellar space, perhaps having been ejected from another planetary system hundreds of millions of years ago, or longer. The fact that it arrived in the inner solar system from the general direction of the solar apex only strengthens this conclusion, as this is where we might expect interstellar comets to come from. Meanwhile, as of this writing, additional observations continue to support the hyperbolic orbit, however very deep imaging with very large telescopes has failed to reveal any signs of cometary activity, and thus it has been reassigned the designation A/2017 U1 (the "A" indicating the object is an asteroid that happened to be assigned a cometary designation). Regardless of what the object's true physical nature turns out to be, this clear detection of an apparent escapee from another planetary system is a most important discovery, and among other things tells us that the processes that go on in our solar system go on in other planetary systems as well. For what it's worth, the small perihelion distance, as well as the even closer approach to Earth's orbit -- indeed, it passed only 0.16 AU from Earth itself on October 14 -- brings to mind, and indeed is eerily reminiscent of, the "Rama" vehicle in the 1973 Arthur C. Clarke novel "Rendezvous with Rama," which passed through the inner solar system on a similarly hyperbolic orbit.

The newest addition to my comet tally is another Pan-STARRS discovery, but far more mundane than A/2017 U1. It was found almost two years ago, on November 2, 2015, at which time it was a very faint object near 20th magnitude located 7.4 AU and 7.1 AU from the sun and Earth, respectively. Because of its relatively large perihelion distance I never expected it to get bright enough to detect visually, however some of the recent reports I have read, and some of the recent CCD images I have seen (which show the presence of a distinct tail) suggested it might be worth attempting. After an unsuccessful attempt earlier in October I tried again on the evening of October 22 under very good sky conditions, and seemed to see an extremely faint "something" of magnitude 14 1/2 right near the limit of visibility of my telescope; I detected clear motion over an interval of two hours. On the following night the sky conditions seemed to be even better, and I once again saw the comet, which after an hour moved into a very good location with respect to the surrounding star field; despite its extreme faintness I could detect some structure within the moderately condensed coma, although I couldn't see any sign of the tail.

The comet is currently located in eastern Pisces approximately six degrees west of the star Eta Piscium, and -- traveling in a moderately inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 139 degrees) -- is moving towards the southwest at slightly less than half a degree per day. It remains within Pisces for the next 4 1/2 months, gradually moving over into the south-central part of that constellation. Although it is currently still over a month and a half away from perihelion passage, since it was already at opposition in mid-October and was closest to Earth (3.31 AU) on October 20, it is likely as bright now as it is going to get, and in fact should begin fading within the not-too-distant future. Since it is already near the extreme limit of my detectability, I will at most likely obtain only one or two more observations of it; indeed, it is distinctly possible that the two observations I have now are the only times I will see this comet.

CONFIRMING OBSERVATION: 2017 October 24.17 UT, m1 = 14.5, 0.6' coma, DC = 5-6 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (November 17, 2017): More or less as I expected, by early November Comet C/2015 V1 had faded beyond my range of visual detectability with the 41-cm telescope, and thus the two consecutive-night observations I obtained in October will remain my only sightings of this comet.

Meanwhile, the object designated A/2017 U1 that I discuss at the beginning of this entry continues to make news. Orbital calculations continue to indicate both a "before" and "after" eccentricity near 1.2, confirming that it entered the solar system from interstellar space, and will recede back into interstellar space (in the general direction of the "Great Square" of the constellation Pegasus). The Minor Planet Center has assigned it the permanent designatiuon of "1I" (the "I" indicating it is an interstellar object), and it has been given the name " 'Oumuamua" (from Hawaiian words meaning "a messenger from afar arriving first") by the Pan-STARRS discovery team.

633. COMET P/PHAETHON P/(3200) Perihelion: 2018 January 25.35, q = 0.140 AU

One of the most productive of the space-based astronomy missions that have flown during the past few decades was the InfraRed Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) which, as its name indicates, surveyed the sky at medium- and far-infrared wavelenghts for ten months during 1983. Among its many discoveries were six comets, four of which I have observed: two of these are periodic comets that I have also seen on subsequent returns (126P/IRAS and 161P/Hartley-IRAS), and another was Comet IRAS-Araki-Alcock 1983d (no. 56), which passed just 0.031 AU from Earth in May of that year -- until a year and a half ago, the closest approach to Earth of any comet on my tally -- and which became as bright as 2nd magnitude in the process. Another one of its dramatic discoveries, which took place on October 11 of that year, was of a fast-moving object which Earth-based photographs revealed was a 16th-magnitude asteroid. Designated as 1983 TB, calculations soon revealed that it was traveling in a very elongated orbit (eccentricity 0.89) with an orbital period of 1.4 years and a perihelion distance of only 0.14 AU, the smallest of any asteroid that was known at the time.

This all occurred during a time of significant changes in my personal life. On Thursday, October 20, 1983, I received my discharge from the U.S. Navy, and a few days later I departed for my original home in New Mexico, in part to scout out potential employment and educational opportunities, and also to spend a last few days (and nights) at the house where I had been raised, as my father had just recently sold it and was in the process of moving. At the beginning of November, after one last observing session at my childhood home, I departed on the return trip to California, taking the northern route, i.e., through Flagstaff, Arizona, to scout out potential employment and educational opportunities in that area. One of the places I visited was the U.S. Naval Observatory's station in Flagstaff, and it was on the bulletin board there that I saw the just-issued IAU Circular 3881, wherein Fred Whipple pointed out that the orbit of 1983 TB coincided with that of the Geminid meteors.

The link between comets and meteor showers had long been established for over a century, but the Geminids, which are among the strongest of the "annual" meteor showers -- regularly producing rates as high as 60 to 100 meteors per hour when they peak in mid-December -- were an enigma, in that no parent comet had yet been identified. With Whipple's announcement, it appeared that, at long last, a parent for the Geminid meteors had finally been found. This immediately raised speculation that 1983 TB was not a "true" asteroid, but rather an extinct or dormant comet. A couple of astronomers made attempts to detect cometary emissions from 1983 TB as it headed away from the sun, but these were unsuccessful.

It so happened that on the inbound leg of its next return to perihelion, 1983 TB would pass 0.245 AU from Earth in mid-December 1984. By that time I was working for the Deep Space Network at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and was regularly observing from several of the nearby mountain sites, and since the ephemerides were suggesting that 1983 TB would be bright enough to detect visually, I decided to attempt it. I ended up observing it a handful of times over a two-week period in mid-December, during which time it reached a peak brightness of 13th magnitude and appeared entirely stellar through the 20-cm (8-inch) telescope I was using at the time. Even though it was still approaching perihelion, it began to fade dramatically as its phase angle increased -- exactly as an asteroid would be expected to do -- and by performing a light-curve analysis from my observations and those obtained by some of my colleagues I found that its brightness behavior was entirely consistent with that of a low- to moderate albedo asteroid.

Various other investigations carried out by astronomers all over the world also failed to reveal any signs of cometary activity in 1983 TB. In the February 1985 batch of the Minor Planet Circulars it was assigned the permanent asteroidal number (3200), and five months later it was given the name Phaethon from Greek mythology, "the son of Helios, who operated the solar chariot for a day, lost control of it and almost set fire to the earth."

While carrying out my observations and analysis of Phaethon during its 1984 passage by Earth, I found myself completely caught up in carrying out the research project, which included communication with various colleagues as well as literature searches, and I even conducted broadband filter observations of several asteroids of various spectral types as well as of several comets that were in the sky at the time (including the possible comet-to-asteroid "transition" Comet 49P/Arend-Rigaux (no. 79), which I discuss in its "Countdown" entry for its 2011 return (no. 496)). I ended up presenting my results at the National Astronomy Convention that was held in Tucson, Arizona in June 1985, and the paper I wrote was published in the Proceedings of that conference, my first published research paper. Ever since I had left the Navy I had been consumed by the question of "where do I go from here?" and the entire experience of observing and analyzing Phaethon re-lit a fire within me that had essentially lain dormant since I was in high school, and played a significant role in my decision to go to graduate school and seek my doctoral degree, a decision that would eventually lead to my return to New Mexico in 1986 and my enrollment in the Astronomy Department at New Mexico State University.

Phaethon, of course, has continued to make its regular orbits around the sun and make occasional somewhat close approaches to Earth ever since its 1984 passage. It passed 0.49 AU from Earth in November 1987 and should have reached 15th magnitude according to the brightness formula I derived from the 1984 observations, but during a couple of search attempts I failed to find it. While outbound from perihelion in 1993 it should have again reached 15th magnitude, and in late 1994 it should have reached 14th magnitude while passing 0.44 AU from Earth while inbound to perihelion, however both of these occurrences took place during the period of "displacement" during which I was living in El Paso, Texas, and thus having to transport the 41-cm telescope an hour into the surrounding desert -- something I was reluctant to do except on rare occasions. (I was also hindered by poor weather, and bad timing with regard to moon phases, during the times in question.) I would finally observe Phaethon again in December 2004, when during a distant approach (0.61 AU) to Earth while inbound to perihelion I was able to obtain a single observation of it as a stellar object of 15th magnitude.

Three years later, in December 2007, Phaethon passed just 0.121 AU from Earth, again while inbound to perihelion. I was able to obtain a handful of observations -- during which it again appeared completely stellar -- between mid-November and early December, and it reached a peak brightness of magnitude 12 1/2 before disappearing into the dawn sky. This was during the period during which I was conducting "Countdown," and while I did not include it as a tally entry, I did list it on the "Update" page during the period of time in question.

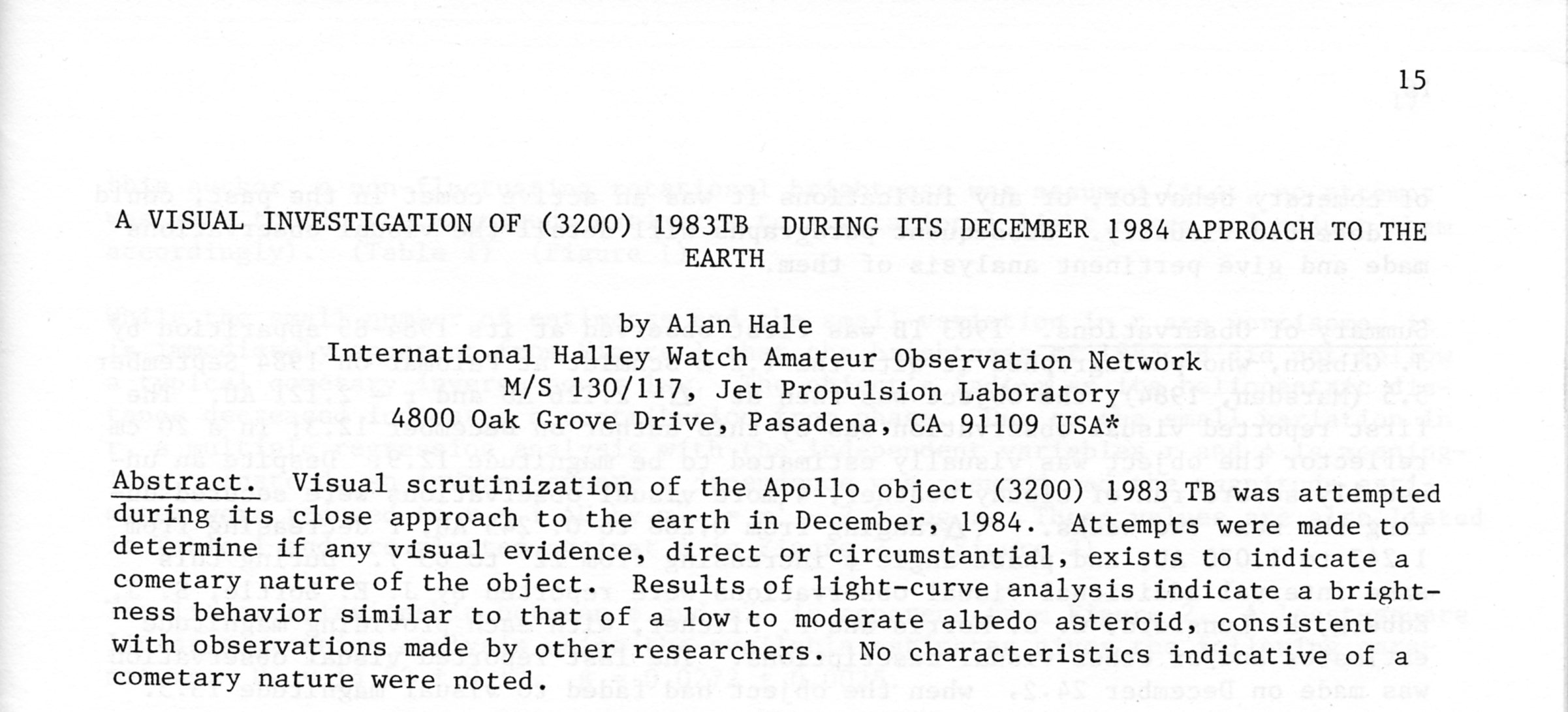

Phaethon's "status," as it were, took a dramatic turn in mid-June 2009 when it was near perihelion passage, when researchers noted that, in images taken with the Heliospheric Imager camera aboard the STEREO-A spacecraft, it was exhibiting a weak coma and tail activity, and furthermore had brightened a couple of magnitudes and was exhibiting a brightness behavior inconsistent with that of an asteroid. Analysis of the data indicated that Phaethon had indeed undergone a release of dust around the time of perihelion. Meanwhile, it exhibited a similar appearance and behavior in the STEREO-A images two returns later, when near perihelion in May 2012. At long last, Phaethon was finally exhibiting cometary activity, although as UCLA astronomer David Jewitt has pointed out, the repeated solar heating that Phaethon experiences during its regular close approaches to the sun would have completely depleted water and other volatile substances, and that the activity we are seeing is instead likely due to sun-baked fracturing of its crust, with dust then being swept away by solar radiation pressure. Jewitt and his colleagues have suggested that Phaethon could be considered a "rock comet," to distinguish it from the more conventional comets that are caused by sublimation of water ice and other volatiles. Jewitt notes, however, that the amount of dust released by Phaethon during its perihelion passages is at least an order of magnitude less than what is required to produce a meteor shower with the strength of the Geminids, and thus it is entirely possible that Phaethon was a more conventional comet in the past.

After all this, I was left with the question of whether or not a "rock comet" could be considered a "comet," at least for purposes of my tally. As I was working on my auto-biography, I decided I could justify the answer as being "yes," especially after considering Phaethon's activity near perihelion, its association with the Geminids (and thus the likelihood that it was indeed a more traditional "comet" in the past), and the fact that other "dusty" non-volatile objects had been assigned periodic comet designations by the IAU. At the end of 2014 I thus retroactively added to my tally the three returns during which I had observed Phaethon: the observations I obtained during its 1984 approach to Earth constituted tally entry no. 559, the single observation I obtained in 2004 was tally entry no. 560, and the observations I obtained in 2007 were tally entry no. 561. In all three cases, perihelion passage took place early the following year.

LEFT: Title and abstract of my paper concerning my observations of (3200) Phaethon in 1984. From Proceedings of the National Astronomy Convention, University of Arizona, 1985. RIGHT: A coma and dust tail on (3200) Phaethon, in a composite image obtained with the STEREO-A spacecraft on June 21, 2009. Image courtesy NASA/Jing Li and David Jewitt (UCLA).

When Phaethon passed perihelion in August 2016 it once again exhibited a diffuse appearance in STEREO images. On its outbound leg it passed 0.40 AU from Earth at the end of September, the best opportunity since its discovery for detecting possible post-perihelion cometary activity from the ground. I managed to observe it (no. 607) on a handful of occasions between late September and late October; on all occasions it appeared 15th magnitude and stellar, and no cometary activity was detected from anywhere.

The stage is now set for what should be one of the best opportunities we'll ever have for examining Phaethon during the foreseeable future. On December 16, 2017, Phaethon approaches to within 0.069 AU of Earth, the closest approach since its discovery, and the 7th closest approach to Earth on any comet on my tally. A wide variety of observations are being planned by astronomers worldwide, including radar bounce experiments from the Deep Space Network's large antenna in Goldstone, California.

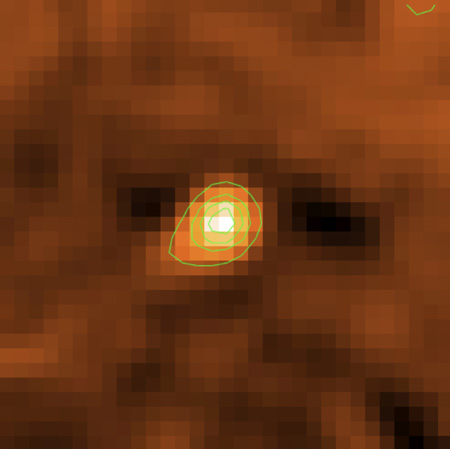

After an unusual run of cloudy weather for this time of year, I successfully picked up Phaethon on my first attempt, on the evening of November 18; it appeared entirely stellar at 15th magnitude. At that time it was located in far eastern Auriga three degrees northeast of the star Theta Geminorum, and since it currently is coming almost directly towards Earth, it is traveling towards the northwest at barely over ten arcminutes per day. As it approaches Earth it rapidly brightens and its daily motion accelerates; by the beginning of December it will be located in central Auriga and traveling close to 45 arcminutes per day, and should be close to 13th magnitude. On December 10 it passes slightly over one degree south of the bright star Capella, at which time it will be close to 11th magnitude and traveling close to four degrees per day. One day later Phaethon crosses into Perseus and is at its highest northerly declination (+45.5 degrees) the day after that (by which time its motion will have increased to six degrees per day and its brightness to magnitude 10 1/2). On December 15 Phaethon crosses into Andromeda, and will be traveling rapidly towards the southwest at 11 degrees per day, and should be near its maximum brightness of 10th magnitude. At the time of its closest approach to Earth Phaethon will be in central Andromeda some five degrees east-southeast of the star Alpha Andromedae (Alpheratz -- the northeastern corner of the "Great Square" of Pegasus) and will be traveling at its maximum rate of 15 degrees per day; because of the rapidly increasing phase angle the brightness should have dropped to about magnitude 10 1/2.

The increasing phase angle continues to take a toll on Phaethon's brightness as it recedes from Earth. Shortly after its closest approach it enters Pegasus, and by the (western hemisphere's) evening of the 19th it will have entered Aquarius and will be crossing the iconic "water jar;" its motion will have dropped to 9 degrees per day, and the brightness to 12th magnitude. By December 22 Phaethon will have entered Capricornus and will have slowed down to just over 5 degrees per day, and will have faded to about 13th magnitude. Within another two or three days Phaethon will have faded beyond the range of visual detectability as it disappears into the dusk.

The close flyby of Earth this time around presents an excellent opportunity for gaining knowledge about this still-mysterious and enigmatic member of our solar system. An even better opportunity for scientific observations should come during the next decade, with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's (JAXA's) Demonstration and Experiment of Space Technology for INterplanetary voYage Phaethon fLyby dUSt science (DESTINY+) mission. According to current plans DESTINY+ is slated for launch in 2022, and via the usage of ion engines will fly to within about 500 km (310 miles) of Phaethon within the subsequent four years.

While Phaethon has now been a part of my life for over three decades, the current flyby of Earth may very well be my "last hurrah" for this object which has had such a profound influence on my life (although I do hope to be around to see whatever results DESTINY+ might provide). It makes a somewhat distant approach to Earth (0.64 AU) in November 2020 but probably won't get any brighter than magnitude 15 1/2; meanwhile, on its outbound leg from perihelion it passes 0.37 AU from Earth in October 2026 and should reach magnitude 14 1/2. Just over a year later, in December 2027, under conditions very similar to those in 1984 it passes 0.27 AU from Earth and should reach 13th magnitude. Both of these latter two encounters take place after the "retirement" timeline that I have discussed elsewhere on these pages, although as I have also stated elsewhere I am uncertain as to how "solid" that "retirement" schedule might be, or even what I might mean by "retirement." In any event, I can say with some certainty that I will never have the opportunity to study Phaethon as well as I should be able to do so on the present return; not until December 2050 does it make a similar close approach (0.083 AU). Phaethon makes an extremely close approach to Earth -- 0.020 AU -- in December 2093, during which it should reach 9th magnitude or brighter, but I sincerely doubt I'll be around to witness that. But perhaps by then we'll have a pretty decent handle as to Phaethon's true physical nature.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2017 November 19.26 UT, m1 = 14.9, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (December 27, 2017): The above brightness scenario pretty accurately described Phaethon's behavior during this close approach. I measured a maximum brightness of magnitude 10.3 on the evening of December 12 before it began a slow, then more rapid, fading over the course of the subsequent week. It appeared completely stellar at all times -- no surprise -- and, as far as I know, every other observer also saw nothing but a stellar appearance.

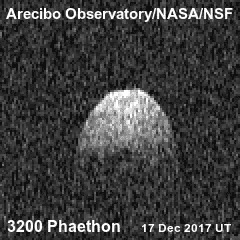

While the above writeup states that radar bounce experiments were being planned from Goldstone, California, it turns out that the radar bounces were performed by the giant radio telescope in Arecibo, Puerto Rico -- the first such experiments since that instrument was damaged by the passage of Hurricane Maria back in September. The radar observations reveal that Phaethon is roughly spherical in shape and about 6 km (3.6 miles) in diameter, and appears to have a conspicuous dark feature -- possibly a crater -- near one of its rotational poles.

LEFT: Phaethon (bright "star" in center) as imaged by the Las Cumbres Observatory global network station at McDonald Observatory, Texas on December 13, 2017. RIGHT: Radar image of Phaethon obtained December 17, 2017 by the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico. Image courtesy Arecibo Observatory/NASA/NSF.

FINAL OBSERVATION: 2017 December 21.10 UT, m1 = 13.4, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

634. COMET HEINZE C/2017 T1 Perihelion: 2018 February 21.71, q = 0.581 AU

The second week of December 2017 has proven to be a rather interesting time for comet observing. The Gemind parent (3200) Phaethon (previous entry) is in the midst of its record-breaking close approach to Earth, being presently around 10th magnitude, and Comet PANSTARRS C/2016 R2 (no. 628) has been unexpectedly bright (close to 11th magnitude) and active despite its current heliocentric distance of 3.0 AU and is showing remarkable structure in its ion tail in some of the recent CCD images I've seen (some of which are strikingly reminiscent of those of the bizarre Comet Humason 1961e from over half a century ago). Meanwhile, in my latest statistical analysis I mentioned that the "Centaur" Comet 174P/Echeclus P/2000 EC98 (no. 384) might undergo additional outbursts in the future; it has just recently done so, and has recently been visible as a small condensed object slightly brighter than 14th magnitude -- the brightest at which it has ever been observed -- despite being over 2 1/2 years past perihelion passage and being located at a heliocentric distance of 7.3 AU.

And, I have just added another comet to my tally. This one comes courtesy of the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) program, developed by the University of Hawaii and presently incorporating telescopes based at Haleakala and Mauna Loa (with more telescopes on a worldwide basis planned for the future). The first ATLAS telescope (Haleakala) went on-line in 2015, with the Mauna Loa telescope becoming operational earlier this year; since first going-on line ATLAS has discovered several dozen near-Earth asteroids and (as of present) eight comets.

The 7th ATLAS comet was discovered by one of the program's astronomers, Aren "Ari" Heinze, with the Mauna Loa telescope on October 2, 2017 (with pre-discovery images later being identified in images taken with the same telescope four nights earlier). The comet was a rather dim object of 18th magnitude located a little over 2.5 AU from the sun at that time, but has brightened steadily during the subsequent weeks as it has approached the earth and the sun. On November 22 I successfully imaged it with the 0.4-meter Sutherland, South Africa telescope of the Las Cumbres Observatory global network -- something I will have more to say about in a subsequent entry -- and its brightness on the image suggested it might be bright enough to attempt visually, but when I attempted to do so six nights later I was unable to see it. On my first attempt of the current dark run, late on the evening of December 12, I successfully observed the comet as a dim, diffuse, slightly condensed object slightly brighter than 14th magnitude. It appeared perhaps a couple of tenths of a magnitude brighter when I saw it again three nights later.

As Comet Heinze pulls away from Earth its motion through the sky starts to slow down, although it continues northward until reaching a maximum northerly declination of +68.9 degrees on January 6, at which time it will be located in northeastern Cassiopeia. Over the next few days it travels southwestward across that constellation, passing two degrees northwest of Beta Cassiopeiae (the westernmost star of the "W") on January 10.

Over the next several days the comet crosses northern Andromeda and then into Lacerta, and begins to travel almost due southward as it descends toward the ecliptic plane on the far side of the sun. By late January it is in western Pegasus, again traveling at 50 arcminutes per day, and it will probably not remain in view for much longer, as it is in conjunction with the sun (32 degrees north of it) in mid-February. By the latter part of March it becomes accessible in the morning sky, being located then in central Aquarius and traveling towards the south-southeast at 40 arcminutes per day; it remains a somewhat difficult object for the northern hemisphere but increasingly becomes visible to observers in the southern hemisphere over the next few weeks as it enters southern circumpolar skies by the latter part of May.

Comet Heinze appears to be rather dim, instrinsically, as long-period comets go, and -- as is always the case anyway for long-period comets -- any brightness predictions must be regarded as uncertain. Based upon the initial brightness measurements I have made, and under the assumption that the comet brightens "normally," it may be as bright as 11th magnitude, possibly 10th, by late December, and may be up to a magnitude brighter when it is nearest Earth in early January. It may then fade by perhaps a magnitude or so by the time it disappears into evening twilight in early February. If it is still visible when it reappears in the morning sky during late March, it is likely to be rather faint -- no brighter than 12th or 13th magnitude -- and it will probably fade beyond the range of visual detectability before much longer.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2017 December 13.29 UT, m1 = 13.8, 0.7' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (April 9, 2018): Comet Heinze appeared close to 10th magnitude when I last observed it in early February, before it began disappearing into evening twilight. It remained near this brightness for another week or so, but according to a couple of observers who were able to follow it right up until perihelion, it apparently began to disintegrate around that time.

The comet has now emerged into the morning sky. Unfortunately, due to its low elevation and to an unusual streak of cloudy weather here in New Mexico, I have not been able to attempt it, but according to reports I've read and images I've seen, the disintegration process has continued; at present, it appears as little more than a vague diffuse patch of light of 16th magnitude or fainter.

For whatever it's worth, Comet Heinze is currently in eastern Aquarius, some three degrees east of the star Delta Capricorni. It is traveling towards the south-southeast at 45 arcminutes per day, and in two weeks crosses into Piscis Austrinus before eventually crossing into Grus in early May, by which time it will be near its closest to Earth (1.30 AU) and traveling almost due southward at one degree per day.

635. COMET CATALINA C/2017 S6 Perihelion: 2018 February 26.93, q = 1.543 AU

As my observing skills have increased over the many years that I have been observing comets, and as the comet discovery rate has increased as well (especially as a result of the comprehensive surveys that have been on-line for the past two decades), the average number of comets that I observe each year has steadily increased. For most of my first decade of comet observing I would usually only reach a maximum of about five comets each year. In 1983 I finally succeeded in reaching double digits (actually observing 11 comets that year), and I have always managed to observe at least 10 comets in every subsequent year. Due to an unusually large number of returning periodic comets I actually succeeded in observing 20 comets the following year (1984), and after achieving that number on an occasional basis for the next decade and a half I began doing so on a regular basis once the comprehensive surveys came on-line in the late 1990s. I hit 30 comets for the first time in 2002 (actually observing 34 comets that year), and ever since then I have managed to observe 30 or more comets during about half of the subsequent years. My current record for most comets in one year is 39, in 2015.

With just over a week to go, I finally managed to observe my 30th comet in 2017, but I had to work for it. The comet in question was discovered on September 30, 2017, by Greg Leonard during the course of the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona, although since it was not readily apparent at discovery as being a comet, it was assigned the name "Catalina" once its cometary nature was established. Being a relatively dim object of 18th magnitude at discovery, and traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 153 degrees), Comet Catalina spent most of the next two months traveling westward through northern circumpolar skies, being at opposition in early November and reaching a peak northerly declination of +65.6 degrees in the middle of that month, before beginning to descend southward in the northwestern evening sky. It brightened slowly during that time -- being closest to Earth (1.21 AU) in late November -- but according to most reports I read it was remaining too dim for worthwhile visual attempts. I made one attempt for it in early December -- the same night I added the previous comet to my tally -- but didn't see anything, and had planned to try for it again before the moon began washing out the evening sky. Before I made that second attempt I read a report and saw images that suggested the comet had recently brightened, and on the evening of December 23, while fighting moonlight and thin cirrus clouds, I saw a very faint (13th magnitude) diffuse object in the comet's expected location that moved as expected during the half-hour that I watched it. On the following night, with perhaps slightly better sky conditions (albeit still with some scattered thin cirrus clouds) but brighter moonlight, I again saw a very faint diffuse object in the right location and with the expected motion, verifying that I had indeed observed the comet.

Comet Catalina is currently located in northern Pegasus near the star Beta Pegasi (the northwestern star of the "Great Square") and is traveling slightly westward of due south at a little under one degree per day. With the ever-brightening moon in the evening sky I am very probably done with it for the current dark run, and will likely not see it again until sometime in early January, by which time it will be well "down" the westward side of the "Great Square" and slowing down as it recedes from Earth. On January 19 the comet passes four degrees west of Alpha Pegasi, or Markab (the southwestern star of the "Great Square") and it will have slowed down to 20 arcminutes per day. How bright Comet Catalina might be during this time is difficult to predict, although I suspect it may be slightly brighter than it is now (since it is still approaching perihelion). Meanwhile, by late January it will be getting quite low in the northwest after dusk, and with the brightening moon in the evening sky at that time I will probably lose the comet sometime during this period.

The comet is on the far side of the sun from Earth at the time of perihelion passage, and is in conjunction with the sun (10 degrees north of it) in early March. By the latter part of April it begins emerging into the morning sky, being located a few degrees east-southeast of the "water jar" in Aquarius, and continues its southward trek over the next several weeks. I suspect the comet will have faded beyond the range of visual detectability by that time, although we won't know that for sure until that time gets here; for what it's worth, observers in the southern hemisphere will have it more easily accessible than will those of us north of the Equator.

CONFIRMING OBSERVATION: 2017 December 25.18 UT, m1 = 13.4, 0.7' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (January 10, 2018): Some images I've seen and reports I've read suggest that the late-December upsurge in brightness that this comet underwent and that led to my successful observations of it may have been due to an outburst, or -- perhaps even more probable -- the first act of disintegration. (This is rare, but not unheard of, for long-period comets approaching perihelion.) Indeed, some of the images I saw that were taken in very late December and just after the beginning of 2018 -- albeit in bright moonlight -- suggested that the disintegration process was continuing. Once the moon had cleared from the evening sky I made an attempt for Comet Catalina on the evening of January 4, and successfully detected it, however it appeared as only an extremely vague, diffuse 14th-magnitude patch of light that was little more than a "presence." An image I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory telescope network a few hours later showed the comet as only a dim, diffuse smudge. It thus appears that this comet may indeed be disintegrating, and I am very probably finished with it.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2018 January 5.12 UT, m1 = 13.8, 1.0' coma, DC = 0 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

636. COMET 185P/PETRIEW Perihelion: 2018 January 27.67, q = 0.934 AU

The New Year of 2018 has now arrived at Planet Earth. While my own personal New Year's celebration was quite enjoyable -- for reasons which I may share at a later time -- the New Year itself has, thus far, been a rather difficult one for me emotionally, as several people, including those I consider personal friends as well as those whom I have admired, have just passed away. This started with former astronaut Bruce McCandless, who passed away on December 21, whom I got to know moderately well as he and his late wife Bernice were part of my second "science diplomacy" visit to Iran, in July 2000. Marie Bakke -- mother of my childhood best friend Mark, whom I discuss quite extensively in my entry for Comet 24P/Schaumasse (no. 631) -- passed away just before New Year's; in a somewhat ironic twist, I made what is probably my last observation of that comet on its current return, and quite possibly my last observation of it ever, just a couple of days before she died.

Just a few days ago I learned that my Hale-Bopp co-discoverer, Thomas Bopp, passed away at the age of 68. He and I had been in occasional contact over the years, and I had last seen him in June 2016 at the SpaceFest conference in Tucson, Arizona (with health issues apparently preventing him from attending the SpaceFest last year, which I did attend). At the same time, I learned that former astronaut John Young, who had walked on the moon as part of the Apollo 16 mission and who, among other flights, also commanded the first Space Shuttle mission, had just passed away. All of the astronauts of that early era were my heroes, and I had the privilege of meeting him once at a Space Frontier Foundation conference in Los Angeles several years ago. And, finally -- I hope! -- I've just learned that Ray Thomas, of the British rock band The Moody Blues -- one of my all-time favorite bands, dating back to my early high school days -- has just passed away. I am glad I was able to attend a couple of Moody Blues concerts (including one at The Greek Theatre in Los Angeles) when I was living in southern California during the early 1980s.

Provided that this rash of deaths can ebb for a while, this New Year of 2018 does show some promise of being an interesting and meaningful year for me. I continue to progress in my "re-engagement" of Earthrise, and I hope I have something to say about that in the not-too-distant future. As far as comets are concerned, 2018 looks to be a very good year: several bright and notable periodic comets are making favorable returns this year -- including one which is coming close to Earth and should reach naked-eye brightness -- and a long-period comet discovered in 2017 also shows some promise of reaching naked-eye visibility (albeit the show will likely be rather brief). On a personal level, if my father, Nile Hale, were still alive, he would be celebrating his 100th birthday in September; he was the person who helped get me interested in astronomy in the first place, way back when I was in Elementary School. And, in a couple of months I will "celebrate" the big 6-0 (ugh!).

As if to set the stage for all the comets that are coming this year, 2018 begins as a rather busy year for these objects. Comet Heinze C/2017 T1 (no. 634) is in the midst of its moderately close approach to Earth, although it has remained somewhat faint, not getting much above 11th magnitude. Comet PANSTARRS C/2016 R2 (no. 628), also currently near 11th magnitude, has been found to be unusually rich in ionized carbon monoxide, and has been exhibiting enormously dynamic activity in its ion tail. Amongst these and others, I have also added my first two tally additions of the New Year, both on the evening of January 5; this is the 33rd occasion during my years of comet observing wherein I have added two or more comets to my tally on the same night.

The first of the tally additions is an old friend, which was originally discovered in August 2001 by a Canadian amateur astronomer, Vance Petriew, and which I successfully confirmed (no. 294) the following morning both visually and with the CCD system which was operational at the time, becoming -- much to my satisfaction -- the first person in the world to obtain accurate astrometry on it and being so listed in the discovery announcement. It was found to have the relatively short orbital period of 5.5 years, and I had successfully observed it on both subsequent returns, in 2007 (no. 400) and in 2012 (no. 506); I discuss it somewhat extensively in its "Counting Comets" entry for the latter return. Earlier that month I had experienced the (first) breakup of my previous relationship, and was emotionally devastated in the aftermath; my observations of Comet Petriew, although they were few in number, helped in setting me on the long and difficult road to healing.

On its current return Comet Petriew was recovered on July 18, 2017 by Jean-Gabriel Bosch and Alain Maury from the Observatoire de la Cote d'Azur's San Pedro facility in Chile's Atacama Desert. It was reported as a very faint object of 20th or 21st magnitude, and it apparently remained quite faint for the next several months, as only a handful of observations were reported. I successfully imaged it (in bright moonlight) in early December with the Las Cumbres Observatory network, although it appeared as little more than an extremely faint and tiny smudge of light, and then made a couple of unsuccessful visual attempts later in December. When I made my first attempt of the current dark run I successfully observed it as a vague and diffuse object slightly brighter than 12th magnitude, located well within the zodiacal light.

The current return is similar to, albeit slightly better than, the return in 2007. The comet is currently located in central Aquarius, at an elongation of 41 degrees and about six degrees east of the star Xi Aquarii, and is traveling slightly northward of due east at just over one degree per day (passing just over 15 arcminutes north of the star Theta Aquarii on January 12). As it approaches the sun and Earth its apparent motion gradually accelerates and its elongation gradually increases; meanwhile, it crosses into western Pisces at the end of January and into western Cetus a week and a half later. The comet is nearest Earth (1.33 AU) just after mid-February, at which time its elongation will have increased to 47 degrees and it will be exhibiting its maximum apparent motion of 75 arcminutes per day; on the 17th it passes 50 arcminutes south of the Local Group galaxy IC 1613. Afterwards it briefly crosses the southeastern corner of Pisces before crossing back into Cetus near the beginning of March, where it remains for the next few weeks.

Based upon its behavior at previous returns, I expect Comet Petriew to brighten gradually over the coming weeks, to a peak brightness of about 11th magnitude, perhaps slightly brighter, in late January and early February. Afterwards it should begin fading, and I expect to lose it by sometime in early March.

With its present orbital period future returns of Comet Petriew will continue to alternate between morning sky and evening sky, with the morning sky returns becoming progressively less favorable and the evening sky returns becoming more so. I should still be able to observe it during its next return in 2023 (perihelion mid-July), but whether or not I'm still observing comets at the return after that (perihelion late December 2028, and during which it approaches to 0.87 AU of Earth) remains to be seen. A series of close approaches to Jupiter during the mid-21st Century will increase the comet's perihelion distance to slightly over 1.4 AU by the end of the Century, but of course I will be long gone by then.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 January 6.08 UT, m1 = 11.7, 1.7' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

637. COMET JACQUES C/2017 K6 Perihelion: 2018 January 3.14, q = 2.003 AU

Throughout "Countdown" I made frequent reference to the Siding Spring Survey based in New South Wales which, as the only comprehensive survey program based in the southen hemisphere, contributed a non-trivial number of comets to my tally. With the demise of the Siding Spring Survey due to lack of funding in mid-2013, there has been a significant "hole" in the amount of sky that has been searched for comets and near-Earth asteroids. There have been a couple of efforts by amateur astronomers in the southern hemisphere to take up some of the slack; for example, my friend Terry Lovejoy in Queensland, who contributed two of my comets in "Countdown" (including no. 500) and an additional entry in "Counting Comets" (no. 532), has found two more since then, including C/2014 Q2 (no. 556) which became a naked-eye object of 4th magnitude in late 2014 and early 2015, and C/2017 E4 (no. 617) which briefly reached close to magnitude 6.5 last April.

At this time the most productive effort in the southern hemisphere is the Southern Observatory for Near Earth Asteroids Research (SONEAR) program, operated by a group of Brazilian amateur astronomers and based in Oliveira, Minas Gerais. Since becoming operational around the beginning of 2014 SONEAR has thus far discovered six comets and almost 30 near-Earth asteroids (as well as several main-belt asteroids). Half of SONEAR's comet discoveries have been made by Cristovao Jacques: his first one, C/2014 E2 (no. 540), reached 6th magnitude and briefly flirted with naked-eye visibility in mid-2014, and a little over a year later his second one, C/2015 F4 (no. 574), peaked at 11th magnitude.

Cristovao discovered his third comet on May 29, 2017; at that time it was a faint object of 18th magnitude, located in southern circumpolar skies at a declination of -57 degrees. It traveled southward from that point as it slowly brightened, eventually reaching a peak southerly declination of -81 degrees at the beginning of October before turning back northward. It was still at a declination of -68 degrees when I imaged it remotely on November 24 with the Las Cumbres Observatory network; its brightness on the image suggested it was approaching the point of visual detectability, and indeed I soon began to read of visual observations from the southern hemisphere. The comet finally became accessible from my latitude in late December, however by that time there was already significant moonlight in the evening sky, and that (as well as some cloudy weather) precluded any attempts. Finally, on the evening of January 5, 2018 -- not much more than half an hour after obtaining my first observation of the above comet -- I successfully observed Comet Jacques not too far above my southern horizon (at a declination of -41 degrees). It appeared relatively small and condensed, and was slightly brighter than 14th magnitude.

The comet has just recently passed through perihelion, and was also nearest Earth (1.82 AU) shortly after mid-December, and thus is likely

already as bright as it is ever going to get. It is presently located in southwestern Fornax, some three degrees north of the star Phi Phoenicis -- and, from my latitude, already at its highest above the horizon by the time darkness falls -- and is traveling slightly eastward of due north at 45 arcminutes per day. It crosses into southeastern Cetus at the end of January and then into northwestern Eridanus in mid-February, where it remains for the next few weeks. By sometime around that time I suspect it will have faded beyond the range of visual detectability.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 January 6.10 UT, m1 = 13.8, 0.8' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

638. COMET PANSTARRS C/2016 N6 Perihelion: 2018 July 18.21, q = 2.669 AU

A few entries back I commented on a "trio" of unrelated long-period comets, all discovered by Pan-STARRS in mid-2016, and all passing through perihelion in mid-2018 at heliocentric distances between 2.2 and 2.7 AU. I picked up the first two comets of this "trio" within two days of each other last September: C/2016 R2 (no. 628) is now well placed for observation in the evening sky, at 11th magnitude, and has been found to be a member of a rare chemical class of comets and has been exhibiting very dynamic evolution of features in its ion tail; meanwhile, C/2016 M1 (no. 629) remained faint at 14th magnitude up through early November, by which time it was becoming inaccessible low in the western sky. It was in conjunction with the sun (33 degrees north of it) in late December and is now beginning to emerge into the morning sky; I hope to pick it up again (at, presumably, a brighter magnitude) sometime within the next month.

With the addition of this comet to my tally, the "trio" is now complete. Chronologically, it is the middle comet of the "trio," both in terms of its discovery (which took place on July 14, 2016) and its perihelion passage. I began searching for it in June 2017 and made a handful of attempts up through mid-October; I had an extremely faint suspect on an occasion or two but nothing I could ever verify. After conjunction with the sun (63 degrees north of it) in early November it began to emerge into the morning sky by late that month, and I made a handful of additional attempts through mid-December; once again I had very faint suspects on a couple of occasions but could never verify these. Finally, on my first attempt of 2018, on the morning of January 15 (after the moon had cleared from the morning sky), I clearly saw the comet as a small, faint, moderately condensed object slightly brighter than 14th magnitude that exhibited clear motion over a period of an hour and a half.

The comet is presently located in eastern Draco approximately two degrees west of the star Theta Draconis and, traveling in a steeply inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 106 degrees), is moving almost due northward at a little over 20 arcminutes per day. It soon enters northern circumpolar skies, crossing into southern Ursa Minor in early February and passing just five arcminutes west of the star Gamma Ursae Minoris ("Pherkad," the southern and dimmer of the two stars at the end of the Little Dipper's "bowl") on February 16 and then 45 arcminutes northeast of Beta Ursae Minoris ("Kochab," the brighter of the Little Dipper's "bowl" stars) six days later. The comet reaches its maximum northerly declination, +80.5 degrees, in mid-March, at which time it is also at opposition, and possibly a magnitude or so brighter than it is now. By early April it begins a strong southward plunge through Camelopardalis and Lynx, and may fade slightly by the time it disappears into the northwestern dusk in early June.

Comet PANSTARRS is in conjunction with the sun (10 degrees north of it) in late July -- shortly after perihelion passage -- and begins to emerge into the morning sky by mid-September, at which time it will be located in eastern Cancer some five degrees southeast of the Praesepe (or "Beehive") star cluster M44. For the most part it continues its general southward plunge, crossing into western Hydra -- just east of the "head" of that constellation -- in early October, before making a westerly turn and crossing into Puppis in early December. The comet is actually closest to Earth (2.37 AU) on December 24 shortly before it crosses into northeastern Canis Major just before the end of the month. It is at opposition during the first week of January 2019, by which time it is traveling just south of due westward, and it passes 20 arcminutes south of the center of the star cluster M41 on January 16. Up until about this time the comet may have maintained something close to the brightness it exhibited throughout most of 2018, however once it passes through this opposition and thus is pulling away from both the sun and the earth, I suspect it will begin to fade rapidly, and I will probably lose it within another month or so.

As I was preparing this entry, Clarice Stone, mother of my friend and companion Vickie Moseley, passed away on January 16 at the age of 88, after a fairly long illness. Coincidentally, that same day is my older son Zachary's birthday; he has just turned 31. Time does not stop as the circle of life continues on: the number of years that have elapsed since Zachary was born serves to remind us of the amount of time that we have already spent on this planet, and Clarice's death reminds us that our remaining time is finite, and that we need to do whatever we can to make our time here on Earth count.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 January 15.47 UT, m1 = 13.7, 0.5' coma, DC = 6 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (September 20, 2018): Following its recent conjunction with the sun, I successfully picked up this comet in the pre-dawn sky on the morning of September 18, when it was located in central Cancer some six degrees southeast of the "Beehive" star cluster M44 and somewhat deep in the zodiacal light; it appeared as a small and moderately condensed object of magnitude 13 1/2, marginally fainter than it was when I last observed it in the evening sky in early June. It should hold pretty closely to the scenario described above for the next few weeks and months.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2018 September 18.46 UT, m1 = 13.5, 0.4' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

639. COMET 37P/FORBES Perihelion: 2018 May 4.12, q = 1.610 AU

Almost three months elapsed between the addition of the previous comet to my tally and this one. In the early years of my comet observing, going three or more months between successive tally additions was not at all unusual; we knew about far fewer comets than we know about nowadays, the equipment I had access to was not what it is now, and I was still working on developing my observing skills. These days, however, it is unusual; as I recount on my statistics page, the average wait time between successive additions is 28 days, and the median wait time is less than 18 days. Still, as what happened here, every once in a while I will go three months or more without adding a comet to my tally, although this is the longest wait time between successive additions I have had in almost six years. Among other things, during these past three months I have "celebrated" by 60th birthday (ugh!) and have just launched the new "Comet Resource Center" on this web site.

The comet that ended this long wait is an old friend that I have seen on three previous returns. It was originally discovered in August 1929 by a South African amateur astronomer, Alexander Forbes, who discovered four comets between 1928 and 1932 (during which time he was in his late 50s and early 60s -- a fact not lost on me considering my present age). His first comet was the object now known as 27P/Crommelin, a Halley-type comet which I observed in 1984 (no. 64) and in 2011 (no. 489). His second comet, this one, has an orbital period that has varied between 6.1 and 6.4 years in the decades since then, and his last two were long-period comets.

P/Forbes had a reasonably favorable return in 1974, which was early in my comet-observing years; unfortunately, I never looked for it, and with a peak brightness between 12th and 13th magnitude it would have been, at best, a very difficult target for the 4.5-inch (11 cm) reflector I had at the time. It returned again in 1980; earlier that year I had graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, and during the summer I purchased -- as a graduation present to myself -- the Meade 8-inch (20 cm) reflector that would be my primary observing telescope for the next few years. One evening during July my best friend Mark Bakke (whom I discuss in an earlier entry) and I took my new telescope on a camping trip into the Sacramento Mountains, and in an effort to test its capabilities we looked at several faint deep-sky objects, and in the process I also attempted this comet, and successfully picked it up at 13th magnitude (no. 36); this would be the first of many comets I have observed with that telescope. I would observe the comet one more time from New Mexico during that return, and an additional time from southern California after I transferred there to my first Navy duty station.

The comet was poorly placed in 1987 and I didn't look for it. The 1993 return was also quite unfavorable for the northern hemisphere, although I did look for it once. The subsequent return in 1999 was quite favorable, and I first picked it up on March 21 of that year (no. 262); most remarkably, until that time no one else had reported any observations of any kind at that return. I had thus accomplished a very rare feat in this day and age: a visual recovery of a returning periodic comet! The IAU had ceased recognizing "routine" recoveries of periodic comets a few years earlier, and thus I never received any formal credit for this, although in a private conversation later that year with Minor Planet Center then-Director Brian Marsden he informed me that, if the IAU had continued officially recognizing such recoveries, I would have been duly credited.

The comet reached 12th magnitude in 1999, and I followed it up until the time I left for my first "science diplomacy" visit to Iran. The following return in 2005 was also quite favorable, and I followed it (no. 373) for three months as it reached a peak brightness of 13th magnitude. The 2011 return was unfavorable and I didn't look for it. On its present return P/Forbes was first recovered on December 18, 2017 by an American amateur astronomer, Kim Breedlove, utilizing a remotely-operated telescope at the Slooh Observatory's facility in Chile. After one unsuccessful attempt for it in late March I successfully picked it up on my first attempt of the following month, on the morning of April 11; it appeared as a vague, diffuse object of 13th magnitude.

The viewing geometry this year is very similar to that in 1999, in fact, the corresponding perihelion dates for the two returns are identical. However, an approach to Jupiter of 0.56 AU in October 2001 increased the orbital period from 6.1 years to 6.4 years and the perihelion distance from 1.45 AU to near its present value, and thus in general the comet stays farther from the earth and sun than it did in 1999 (although, curiously, the closest approach to Earth is marginally smaller this year than it was then). At present it is fairly low in my southeastern sky before dawn, being located in central Capricornus; for the next few months it remains in my southeastern morning sky, traveling towards the east-northeast at approximately 40 arcminutes per day, crossing into eastern Aquarius in early May and into southwestern Pisces towards the end of June. Around that time the comet should be near its peak brightness, perhaps a half-magnitude or so brighter than it is now.

The comet remains in Pisces for the next several months, as it begins retrograde (westward) motion shortly before the end of July. It is nearest Earth (0.98 AU) in mid-August and is at opposition in early September, however I suspect that sometime during this period of time it will have faded from view.

More than likely, this year's return will be my last for P/Forbes. The next two returns (October 2024 and March 2031) are relatively unfavorable, and while the return in 2037 (perihelion in early September) is moderately good, I consider it doubtful if I'll still be observing faint comets at age 79, which is well beyond the "retirement" timeline I have discussed elsewhere. So, it would seem that whatever observations of P/Forbes I am able to obtain this year will put the finishing touches on an otherwise unremarkable comet that has nevertheless played a couple of interesting roles in my comet observing "career.".

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 April 11.47 UT, m1 = 13.0, 1.0' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

640. COMET 66P/DU TOIT Perihelion: 2018 May 19.16, q = 1.290 AU

After going almost three months before adding the previous comet to my tally, I only had to wait one week before adding this most recent one. While I might hesitate to call it an "old friend," it is nevertheless a comet with which I have previously crossed paths.

The comet was discovered in May 1944 by Daniel du Toit, an astronomer at the Boyden Observatory in South Africa (at that time under the control and ownership of Harvard College Observatory); while there he discovered a total of five comets between 1941 and 1945, three of which are numbered short-period comets, and his last one (1945g) being a Kreutz sungrazer. It passed perihelion the following month (and passed 0.50 AU from Earth in the process), and remained close to 10th magnitude for two months; it was in southern circumpolar skies for much of that time and observations were only possible from the southern hemisphere. When it finally did become accessible from the northern hemisphere several months later it had faded beyond the range of visual observations.

The comet was recognized at the time as being a short-period one, with an orbital period of slightly under 15 years (currently, 14.90 years). The viewing geometry in 1959 was rather mediocre, and despite several search attempts it was not recovered. The viewing geometry in 1974 was similar to that in 1959, and once again several search attempts were unsuccessful, however a year later a couple of images of it were identified on two of the search photographs, and it was thus belatedly "recovered."

The viewing geometry in 1988 was very poor, and again the comet was not recovered. The following return, in 2003, provided the best viewing conditions since 1944, and it was indeed duly recovered early that year. Around mid-year some observers in the southern hemisphere began reporting visual observations near 13th magnitude, and consequently I made an attempt for it in late July; despite its location very low in my southwestern evening sky I successfully picked it up (no. 337) on that single occasion as a vague and diffuse object of 13th magnitude.

The present return of P/du Toit is the most favorable one since the discovery return in 1944. It was recovered on January 14, 2018 by Japanese amateur astronomer Hidetaka Sato utilizing a remote-controlled telescope near Mayhill, New Mexico, and independently four days later by Francois Kugel at the Observatoire Chante-Perdrix in Dauban, France. It was reported as being a very faint object of 19th or 20th magnitude at the time, and for some time thereafter various images I had seen suggested it was remaining faint, however within the fairly recent past it has begun showing signs of a rapid brightening, and very recently there have been reports of visual observations by observers in the southern hemisphere. The comet is very low in my southeastern sky before dawn, and I made one unsuccessful attempt for it shortly before mid-April; a week later, on the morning of April 18, I successfully picked it up as a vague and diffuse object close to magnitude 12 1/2. Its elevation above the horizon at the time was only 7 degrees, and that, combined with its vague and diffuse appearance, made it quite a bit more difficult to see than that brightness would suggest.

Even though I have just picked up Comet P/du Toit, I may lose it soon, at least temporarily. At present it is located in southern Microscopium at a declination of -40 degrees, and is moving almost due eastward at slightly over one degree per day; the sun, meanwhile, is rapidly traveling northward, with the result being that the interval between comet-rise and sunrise shrinks, to the point that by early May the comet will not rise until the beginning of astronomical twilight from my latitude. Observers in the southern hemisphere should be able to follow it rather easily in May, with its passing 0.90 AU from Earth just a couple of days before its perihelion passage. It should reach a peak brightness between 11th and 12th magnitude during this time as it continues traveling eastward through Microscopium, Grus, and Piscis Austrinus.

While I thus probably won't be able to follow the comet during May, it does start to turn northward during this time, and by early June (when it will located in Sculptor) it will be at a declination of -30 degrees. By later in the month it will be 12 degrees or higher above the horizon at the start of astronomical twilight from my latitude and thus accessible for me again; on the 21st it passes half a degree north of the bright spiral galaxy NGC 253 as it crosses into southern Cetus. The comet remains in that constellation for the next several months, being at its stationary point and beginning retrograde (westward) motion at the end of July and passing through opposition in late September, when its declination will be -11 degrees. At some point during this period I should lose it entirely as it fades from view.

It is not lost on me that this comet was discovered during some of the darkest days of recent human history. Many nations of the world were involved in the global conflict known as World War II -- indeed, my father was a veteran of that war, and at the time of this comet's discovery was just a few months younger than my younger son Tyler's present age (he having just turned 26) -- and the invasion of Normandy began just three weeks after the comet's discovery. South Africa was perhaps less affected by the happenings of World War II than other parts of the world, which probably contributed to the atmosphere that allowed such astronomical activities to take place, but we should keep in mind that many would-be astronomers in those other parts of the world weren't so fortunate.

To some extent, the same is true nowadays. I have been fortunate that, for most of my life, I have been able to engage in my passion for comet observing relatively unhindered by the goings-on elsewhere in the world, but I fully recognize that there are many other people in various parts of the world who might share similar passions but who are unable to pursue them due to war, poverty, violence, disease, and other symptoms of the less-than-perfect human society that we live in. My ultimate goal for Earthrise is to contribute to the development of a society where all people, everywhere, are free and able to pursue their passions, be they astronomy or whatever, in an environment of peace and freedom.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 April 18.46 UT, m1 = 12.3 (extinction corrected), 1.7' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (June 27, 2018): According to reports from observers in the southern hemisphere, this comet reached a peak brightness between magnitudes 10 and 10 1/2 around the time of its perihelion passage last month, appearing quite diffuse and vague the entire time. It has now become accessible from my latitude again, and on the morning of June 19 I successfully picked it up low in my southeastern sky just before dawn; it appeared as a large, vague, diffuse object of 11th magnitude, consistent with the reports from the southern hemisphere, which also indicate a recent slight fading.

As indicated above, the comet is currently in southern Cetus, and it remains in this constellation for the next few months, being at its stationary point near the end of July (when it will be located some four degrees west of the star Tau Ceti) and beginning retrograde (westward) motion thereafter. Since it is receding from both the sun and the earth I will probably lose it within the next month or so.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2018 June 19.43 UT, m1 = 10.8, 4' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

<-- Previous

Next -->

BACK to "Comet Resource Center"